Santo Di Nuovo & Rossana Smeriglio

University of Catania – ITALY

The Didactic at Distance (DaD) aims at fostering students’ learning experience and effectiveness in terms of the achievement outcome (Davis & Wong, 2007). Due to pandemics, Dad shifted from additional to unique means for teaching and learning. During the worldwide lockdown, higher educational institutions had to switch their activities from the classroom to a virtual space. This was the only alternative to a complete impossibility to perform the usual activities (Crawford & al., 2020; Kamarianos & al. 2020). The phenomenon started during the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring-summer 2020 semester, lasting till the second semester of 2021.

DaD can foster achievement and academic success, depending on several technical and contextual variables:

– Acceptability of distance learning methods and their motivations.

– Usability of the technological means, developing adequate skills and competencies.

– Development of appropriate online instruments for the assessment and evaluation of achievement.

– Use of non-verbal communication, centered more on the face and less on the whole body (i.e, gestures, proxemics).

– Management of emotions: they should be encoded and decoded through a screen.

– Restructuring of relations, less based on proxemics and direct contacts.

How DaD can be effective in enhancing students’ achievement during pandemics? The benefits of e-learning have been evaluated in researches precedent to COVID pandemics. But so far, there is no shared consensus on whether the outputs of e-learning are more effective than those of traditional learning formats (Dell & al., 2020; Siddiquei, & Khalid, 2017; Visser & al. 2012).

The most frequently stated benefits are: flexibility (in terms of time and place), cost efficiency, saving time to travel, easy access to learning materials, and for a longer period, the potential to offer personalized learning according to the learner’s specific needs (Al-Qahtani & Higgins, 2013: Paechter, & Maier, 2010; Welsh & al., 2003),

A meta-analysis published by Mothibi (2015), based on a sample of 15 research studies conducted between 2010 and 2013, reported that DaD has a statistically significant positive impact on students’ academic achievements (overall d=0.78). But other studies have demonstrated that there are no significant differences between the work submitted by online and face-to-face students and that methods of instruction and characteristics of learners are more important than the delivery platform (Paulsen, & McCormick, 2020).

Recently, Abu Talib & al. (2021) presented a systematic literature review based on 47 studies, aimed at exploring the transition, in the context of the pandemic, from traditional education that involves face-to-face interaction in physical classrooms to online distance education (in many different fields). The review presents suggestions to alleviate the negative impact of lockdown on education and promote a smoother transition to online learning. In particular, it was found that DaD was thought to enhance attention and efficiency, and help in the learning process. Although students expressed sentiments of missing peerto- peer interaction, the majority were open to DaD and some even preferred it to conventional learning. This may be due to the flexibility, convenience, and low cost of online learning. But some students reported feelings of stress in coping with the pandemic situation, and in adapting to the new learning modalities. To reach more generalized conclusions, more data are needed from a broader range of situations and contexts.

Other authors reported that online environments enhance student-centred activities as well as engagement and active processing. A face-to-face setting is preferred for communication purposes, whereas an online setting is preferred when self-regulated work is required. From this point of view, online learning opens up new ways of experiencing school, but at the same time reduces direct and stimulating participation. Regarding motivation, online learners compared to face-to-face learners reported more benefits in terms of perceived academic challenge, learning gains, satisfaction, and better study habits. Instead, face-to-face learners reported higher levels of environmental support, collaborative learning, and social interaction (Adedoyin, & Soykan, 2020; Pokhrel, & Chhetri, 2021).

Undoubtedly, technology-mediated learning lacks direct social interaction and can negatively influence social aspects of learning processes, e.g., the development of learners’ communication skills. Dad changes relational conditions, including lack of social and cognitive presence and teacher’s involvement, less feedback using cues, and reduced non-verbal support by observing the interactions of others. Technology-mediated teaching and learning require self-directed learning, time management, and autonomous organization skills of learners (Al-Qahtani & Higgins, 2013).

These requirements arise from the conditions of social isolation and lack of direct social interaction, which means that the learner must have a relatively stronger self-motivation to contrast this effect.

Specific technical obstacles most reported are many distractions and difficulties to concentrate; too much screen-time; shortage of logistical infrastructure; non-adequate learning environment at home; more workload; loss of labs and practical activities (Owusu-Fordjour & al., 2020).

Emotional aspects involved in the relation between e-learning and achievement, e.g., a general influence of anxiety in online students have been described in empirical research. Students’ feelings of anxiety are negatively associated with their satisfaction with online learning. A negative relationship was found between test anxiety and computerized testing performance, more than in exams in presence (Abdous, 2009).

These emotional aspects can reflect on the performance in the scholastic tasks and examinations.

Moreover, other variables can influence the effects of the learning at distance: personality factors (Farsides, 2003: Laidra, & al., 2007; Poropat, 2009); Emotional Intelligence (Barchard, 2003; Elias & al., 1997; Parker & al., 2004; Petrides & al., 2004; Salovey & Skluyter, 1997); demographic factors (e.g., residence, gender). About the latter variable, it is a constant in the literature that women report worse mental health outcomes as a consequence of prolonged stressors. Even during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first data collected by the researchers highlighted this trend, manifesting more anxiety and depression in women (Casagrande & al., 2020). But the lockdown and pandemic conditions due to COVID-19 seem to have reduced the gender differences in the perception of happiness and mental health, while they seem to have increased the perception of loneliness experienced by males compared to the pre-pandemic condition. The recent data show that now men and women had similar and significantly lower emotional coping than in the pre-pandemic condition (Rania & Coppola, 2021).

The research

Our study aimed at assessing which variables mainly affect scholastic performance and its variations following the Didactic at Distance (DaD) during the pandemic and the forced isolation.

The upper secondary school was chosen for the study, where the DaD was introduced in a generalized way and maintained for longer than the other levels during the phases of the pandemics.

The main aim of the research was to verify some possible predictors of the academic achievement (or its decrease) of upper secondary school students, following the introduction of distance learning, evaluating two phases:

1) The period during the first lockdown phase (March-June 2020), following the first semester of the 2019- 2020 school year which was carried out face-to-face, and the e-learning was considered only a transitory phase;

2) the first semester of the school year 2020-’21, carried out entirely in DaD and with the uncertainty of whether to continue in the same modality for the entire school year.

Specific aims of the study were to correlate the changes in achievement with demographic variables (gender, place of residence: city or provincial town), and the type of school attended; and to consider some predictors of the variations in achievement over time following the prolonged use of the Dad, i.e.: the attitude towards distance learning; the perception of the change in one’s own situation as a student following didactic changes; personality factors; emotional intelligence; the perception of stress related to the school context; symptoms of anxiety and depression, related in general to the pandemic situation.

Method: Instruments and sample

The following instruments were devised for the assessment of the target variables.

– A questionnaire for the detection of the various personal data (age, gender, place of residence) and school address, and the marks obtained in Italian, Mathematics and Science in 2020 and in 2021. The questionnaire also asked for an evaluation of the distance learning learning experience (on a 5-level scale from „very positive“ to „very negative“, and of the perception of the student general status during the pandemic (changed for the better / not substantially / slightly worsened / very worsened).

– The Self-Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SREIT) by Schutte et al. (1998).

– The short version of the Big Five Factors questionnaire (Ten Item Personality Inventory – TIPI; Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003) for assessing personality variables: agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extraversion, open-mindedness. – Items adapted for high-school students from the Perception of Academic Stress (PAS) (Bedewy & Gabriel, 2015) for the evaluation of school stress.

– The Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS, Henry & Crawford, 2005) for the evaluation of the levels of anxiety and depression referred to the period of distancing due to the pandemics.

The questionnaires were preceded by a request for informed consent, ensuring full anonymity and the possibility to withdraw at any time during the compilation.

The questionnaires were administered to an overall sample of 312 upper secondary school students, 175 males and 137 females, average age 16.15 years, st. dev. 1.61; divided as follows based on demographic variables: 132 residents in a city, 180 in provincial small towns; 65 attending scientific high school, 247 technical or professional institutes.

Results

The difference in the achievement level between the two phases was computed for each student, computing the mean of grades for the main matters of study. Near two thirds of the students (65%) obtained lower average marks in the second phase of DaD, while in the 35% of students the average marks were equal or improved. No difference in the three disciplines considered was found.

The mean difference was highly reduced in 2021 compared with 2020 (mean 2021=6.80; mean 2020=7.20, mean difference -0.40, standard deviation of the difference 0.68; paired t=-10.52, d.f. 311, p<0.001).

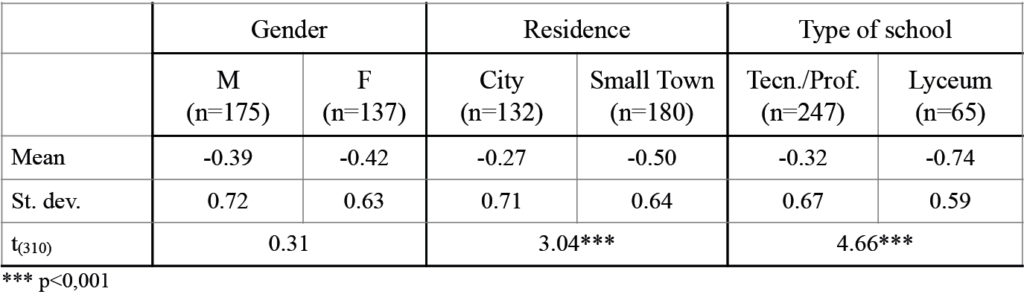

The worsening of the scholastic grades was greater in scientific high schools and in small towns. No significant differences were found by gender (table 1).

The overall differences in the scholastic performances are non-significant related to the perception of DaD (mean difference: 0.15, t=1.05, p>.05), while they were highly significant related to the perception of change in the overall student situation (mean difference: 0.44, t=4.11, p<0.001). This result demonstrated that is not so much the „technical instrument“ that causes the differences in the achievement, but the perception that over time the general condition of the student has worsened substantially with the prolonged social distancing, no longer experienced as contingent and temporary as in the first stage of the pandemics.

As for emotional intelligence (EI), the results were different than those expected: the group whose academic performance deteriorates had a higher average score in EI. This difference does not reach statistical significance (t=1,77, d.f. 310, p=.08), but the trend indicates clearly that more emotionally sensitive students are more prone to worsening academic performance.

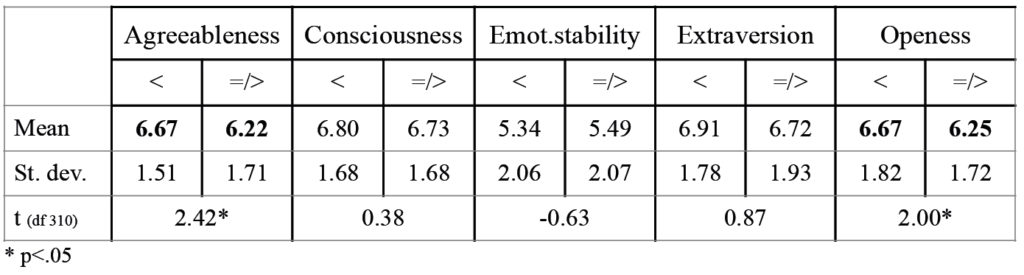

This trend is confirmed by the comparison results relating to personality factors: school performance worsens in students with greater agreeableness and open-mindedness (table 2).

Comparing the change in profit with the variables of anxiety and depression, we found that these stressful aspects of distancing are more difficult to manage in students whose performance has worsened with prolonged lockdown (t=2.31, d.f. 310, p=0.02).

These aspects – related to the general way of managing the stress behavior of the pandemic – seem to have an additional impact on the general deterioration of scholastic performance, regardless of gender (differences among males and females in the relation between emotional variables and achievement are not significant).

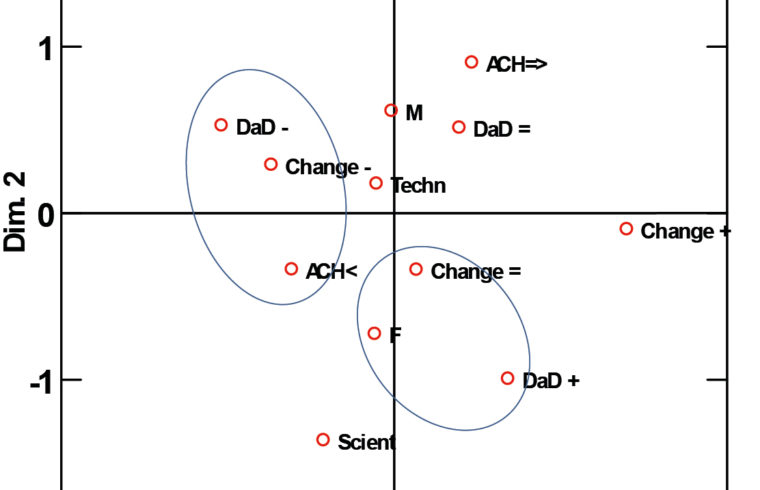

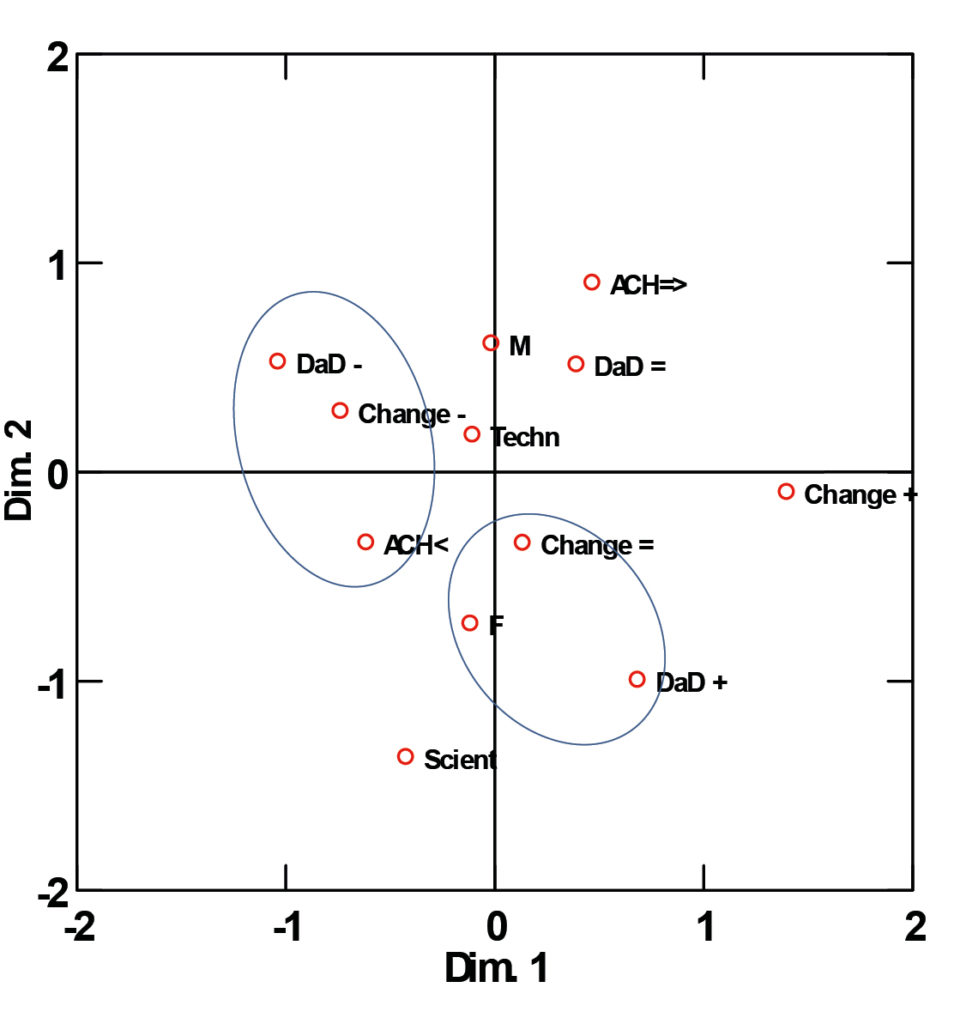

To evaluate the interaction between the categorized variables, a multiple correspondence analysis was performed, simultaneously correlating the gender of the students, the type of school, the change in achievement, the perception of the change in student status, and the attitude towards DaD. The results are shown graphically in fig. 1.

Legend (number of subjects for each category are shown in parenthesis):

Ach => Achievement improved or unchanged (110) / Ach< Achievement worsened (202)

Change + / = / – : perception of the change in student status: + improved (64) / = unchanged (131) / – worsened (117)

Dad + / = / – : evaluation of the Didactic at Distance: + positive (117) / = indifferent (94) / – negative (101) School: Scientific high

School (65) / Technical-professional high School (247)

Gender: M = Male (175) / F = Female (137)

Examining the graph, dimension 1 represents at the negative pole (left) the worsening both in the condition of the student and in DaD perception, while at the opposite pole (right) the unchanged or even improved perception of changes is represented. Dimension 2 has unchanged or improved learning at the positive pole (at the top of the figure), but this outcome is not related to the attitude towards the DaD; while at the negative pole (lower) we find the worsening of profit – also not associated to the DaD, but rather to the type of school (scientific high school)

Crossing the two dimensions, the worsening of learning in the second year of DaD is associated with the perception of a negative change in the condition of the student and DaD. Female students seem to perceive changes less, and experience DaD more positively.

Conclusion

The effects of DaD on academic performance are not generalizable but depend on specific cognitive and emotional factors. A worsening in academic achievement after distancing in learning is mainly linked to the perception of change in the condition of the student, presumably associated with increased tension and a reduced possibility of experiencing positive emotions.

Not only students who show symptoms of anxiety and depression – without relevant gender differences – are most affected, but also those with greater emotional intelligence, more inclined to agreeableness, open-mindedness, and interpersonal and social relationships. These students experience the consequences of the pandemic as more penalizing about their student life.

Beyond the symptoms induced by stress, also some personality traits – generally favorable to cooperative learning success, but now compressed by isolation – have negative consequences in academic achievement that cannot be adequately compensated by distance learning activities.

References

Abdous M. (2019), Influence of satisfaction and preparedness on online students’ feelings of anxiety, The Internet and Higher Education, 34-44.

Abu Talib M., Bettayeb A.M., Omer R.I. Analytical study on the impact of technology in higher education during the age of COVID-19: Systematic literature review. Educational and Information Technologies 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10507-1

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–13.

Al-Qahtani, A. A., and Higgins, S. E. (2013). Effects of traditional, blended and e-learning on students’ achievement in higher education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29, 220–234.

Barchard, K.A. (2003). Does emotional intelligence assist in the prediction of academic success? Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 840-858., 2003

Bedewy D., Gabriel A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The Perception of Academic Stress Scale, Health Psychology Open, 2 (2) https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102915596714

Casagrande, M., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R., & Forte, G. (2020). The enemy who sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Medicine. 75, 12–20.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J.,Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., et al. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning Teaching, 3, 1–20.

Davis, R., and Wong, D. (2007). Conceptualizing and measuring the optimal experience of the eLearning environment. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 5, 97–126.

Dell C.A., Low C., Wlker G.F., Comparing student achievement in online and face-to-face class formats, Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 6, 30-42, 2010

Elias M.J., Hunter L., Kress J.S. (1997). Emotional Intelligence and Education, in Salovey P., Sluyter D., (eds) Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence, New York: Basic Book.

Farsides, T., Woodfield, R. (2003), “Individual differences and undergraduate academic success: The role of personality, intelligence and application”, Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 1225- 1243.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504–528.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales: Construct validity and normative data in a large nonclinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227-239.

Kamarianos, I., Adamopoulou, A., Lambropoulos, H.,

and Stamelos, G. (2020). Towards an understanding of university students’ response in times of pandemic crisis (COVID-19). European Journal of Educational Studies 7:7. doi: 10.46827/ejes.v7i7. 3149

Laidra, K., Pullmann, H., Allik, J. (2007), “Personality and intelligence as predictors of academic achievement: A cross-sectional study from elementary to secondary school”, Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 441-451.

Mothibi G. A Meta-analysis of the relationship between E-learning and students’ academic achievement in Higher Education, Journal of Education and Practice, 6 (9), 6-9, 2015

Owusu-Fordjour, C., Koomson, C. K., and Hanson, D. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on learning-the perspective of the Ghanaian student. European Journal of Educational Studies, 7, 88–101.

Paechter M., Maier B. (2010), Online or face-to-face? Students’ experiences and preferences in elearning, Internet and Higher Education, 9, 292-297.

Parker, J. D. A., Summerfeldt, L. J., Hogan, M. J., & Majeski, S. A. (2004). Emotional intelligence and academic success: examining the transition from high school to university. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(1), 163–172

Paulsen J., McCormick A.C. (2020) Reassessing disparities in online learner student engagement in higher education, Educational Researcher, 49, 20–29

Petrides K.V., Frederickson N., Furnham A., The role of trait emotional intelligence in academic performance and deviant behavior at school, Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 277-293, 2004 Pokhrel S., Chhetri R. A. (2021) Literature review on impact of covid-19 pandemic on teaching and learning.

Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 133-141.

Poropat, A.E. (2009), “A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance”, Psychological Bulletin, 135, 322-338.

Rania, N. and Coppola, I. (2021) Psychological Impact of the Lockdown in Italy Due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Are There Gender Differences? Frontiers in Psychology, 12:567470.

Salovey P. Sluyter D.J. (Eds) (1997), Emotional development and Emotional Intelligence: educational implications, New York: Basic Books.

Schutte N.S., Malouff J.M, Hall L.E., Haggerty D.J., Cooper J.T., Golden C.J., Dornheim L., Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence, Personality and Individual Differences 25, 167-177, 1998

Siddiquei N. L., Khalid R. (2017). The Psychology of E-learning, International Journal of Law, Humanities & Social Science 11–19.

Visser L., Visser Y. L., Amirault R., Simonson M. (Eds.) (2012), Trends and Issues in Distance Education, 2nd ed., Information Age Publishing.

Welsh, E. T., Wanberg, C. R., Brown, K. G., and Simmering, M. J. (2003). Elearning: emerging uses, empirical results and future directions. International Journal of Training Development, 7, 245–258.