Shazia Hasnain

Assistant Professor, Aliah University – INDIA

Santoshi Halder

Professor, University of Calcutta – INDIA

Abstract

The pandemic situation due to Covid -19 led to the complete shutdown of all countries worldwide, and the education sector suffered greatly with the closure of all educational institutes. Students were subjected to a great deal of anxiety and disturbances, which would have a long-drawn effect on their educational and social lives. Studies have been conducted to explore the students’ situation in such a pandemic focusing on their well-being and adjustment to the new mode of learning. The present study collected data from 216 students from different institutions in West Bengal, India assessing their academic and social life. The students’ opinion was sought regarding online teaching-learning and their interaction in social life. It was found that students were overall satisfied with the way online classes were being conducted. A percentage of them were dissatisfied and neutral about the teaching-learning in online mode. Infrastructure at home was adequate for some students, while others expressed dissatisfaction with the infrastructure at home. The study highlights the importance of improving online teaching- learning facilities for those students who had difficulty accessing online learning. The students seem to interact more with their family members and close friends in their social life, which is a good indicator of their well-being. However, they were not comfortable talking or communicating with the lecturers/ teachers and administrative staff, which points out the need to train teachers and staff to deal with students’ mental health problems by communicating with them regularly.

Keywords: Covid-19, India, educational institutes, online learning, academic, social

Introduction

The impact of Covid 19 has been felt worldwide in all areas of human life. The plan of action followed by the different countries for preventing the disease was isolation and social distancing, and it took a toll on people’s lives (Shen et al., 2020, as cited in Singh et al., 2020). The education sector worldwide was affected majorly by the declaration of a complete shutdown of educational institutes. The United Nations (2020) reported that Covid 19 impacted education to a great deal affecting 94% or 1.6 billion students around the world. The Indian education system is the third-largest in the world after the United States and China (Sheikh, 2017), and it was also affected drastically. UNICEF (2021) reported that Covid 19 led to the closure of 1.5 million schools across India, and it affected both teachers and students. This situation led to a paradigm shift in the mode of education at all levels, with online teaching-learning taking centre stage (Bao, 2020; Wang & Zhao., 2020) Online learning emerged as a panacea in the pandemic situation. Ample online platforms were available before the lockdown in universities; however, its full-fledged utility was realized only during the pandemic (Chakraborty et al., 2021; Nash, 2020). According to the UN’s International Telecommunications Union (UNESCO, 2020), 47% of the population from developing countries used the internet, which increased to 86% during the pandemic. Undeniably the pandemic provided people with an opportunity to develop digital learning (Dhawan, 2020), which is the need of the hour. Online education has advantages like control over the content and adapting the process of teaching-learning according to learners‘ needs (Suresh et al., 2018). On the other hand, online teaching also has challenges like “accessibility, connectivity, lack of appropriate devices, social issues represented by the lack of communication and interaction with teachers and peers” (Aboagye et al., 2020, as cited in Coman et al., 2020).

With the adherence to government guidelines, online teaching-learning began that subsequently revealed the disparity existing in the society between the privileged who have internet access and devices for online classes and the ones who have none of the facilities for attending the online classes (Bania & Banerjee, 2020; Dreesen et al., 2020). Kundu 2020 (as cited in Agoramoorthy, 2021) emphasized the poverty prevalent in India, particularly in the rural areas where there is a slow network and students are unable to access online education. This disparity led to many being deprived of education during this pandemic, and subsequently, the Right to Education of students was violated. According to Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, “Everyone has a Right to Education,” and Article 13 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966 states that “Higher education shall be made equally accessible to all…”, however, the pandemic situation manifested itself and showed that practically education became inaccessible for many. This resulted in anxiety and mental stress among the students (Cao et al., 2020; Chorpita et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2020).

With the emergence of the pandemic, students’ stress and anxiety aggravated, affecting their mental health (Salari et al., 2020). Studies have established that higher education students are stressed due to one reason or the other (Edjah et al., 2020), the main stressor being academic demands (Pascoe et al., 2020), inadequate educational facilities, and long hours of study (Yikealo et al., 2018). Higher education students are usually concerned about completing their studies and pursuing higher education or getting a job (Ranta et al., 2020; Chandasiri, 2020) and this stress increased for many during the pandemic. With complete dependence on online teaching and the unavailability of adequate resources at home, the classes for many were not a smooth experience. In some countries, the students have shown increased levels of symptoms of anxiety and depression during the pandemic, such as the study on students from North America and Europe (Nelson et al., 2020) and China (Cao et al., 2020).

In a developing country like India, it was the first time that online education had been tried at a massive level (Muthuprasad et al., 2021), and considering there were many technical constraints and a lack of appropriate resources, it was pertinent to find out college and university students’ opinion about their academic and social life.

Studies on the impact of Covid 19

on the students’ academic life

With the advent of Covid 19, several studies have been conducted worldwide on the impact of the pandemic on the life of school, college, and university students. The present study reviewed some works focused on the higher education students’ situation during the pandemic. It aided in developing an insight into how the pandemic has impacted the students’ academic and social life.

Higher education students feel stressed due to their academics, and as Yang et al. (2021) stated that “students have academic stress and academic stressors refer to academic demands (environmental, social or internal demands) that cause a student to adjust his or her behavior.” With the change in the education world, academics were not the same for students, and their causes of academic stress too changed in nature.

Aristovnik et al. (2020) conducted a study on a large scale whereby data was collected from higher education students in different countries worldwide. The study reported that the most dominant forms of online lectures were real- time video conferences. In this study, the students reported positively regarding lectures, seminars, tutorials, and mentorship. At the same time, dissatisfaction was prevalent in countries and rural areas inflicted with poverty, leading to a lack of online teaching-learning facilities. Students also reported that though well-adjusted to the new online teaching, they had difficulty focusing during online instruction.

Another study by Radu et al. (2020) reported the impact of covid 19 on engineering students in Romania. The results indicated that students were satisfied with the measures taken for online teaching, but some expressed dissatisfaction with the online teaching process. Some reasons for dissatisfaction listed were lack of infrastructure, inadequate practical classes, and a sedentary lifestyle leading to health issues.

Muthuprasad et al. (2021) conducted a study on agricultural students and found that most of them were adjusted to online classes. Only rural students with unstable internet faced a problem in online classes. Students preferred recorded lessons with quizzes at the end for effective learning. Practical classes were not suitable in the online mode, so a hybrid mode of classes was suggested in the study.

Impact of online teaching

on interaction

Qamar and Bawany (2021) conducted a study on the undergraduates in the universities of Pakistan and found that both the teachers and students were concerned about the lack of interaction. Teachers could not gauge the level of understanding the students had about the topic as they were reluctant to interact. The same situation was revealed by Chakraborty et al. (2021), who conducted a study on undergraduates in India and concluded that most students preferred not to show themselves in online classes and were reluctant to answer questions. Overall, students considered online classes to be a viable option for education. But they emphasized that online classes were stressful, affecting their health and social life. Students in the study by Radu et al. (2020) reported the negative aspect of online teaching being the lack of communication between teacher and students and overall lack of socialization. A study on Saudi Arabian university students (Alghamdi, 2020) found that social interaction was promoted to some extent in online teaching, which was a positive aspect. Students indicated high to moderate agreement with the positive and negative impacts of covid 19 on their social and educational aspects of lives.

As widespread studies have covered the impact of the pandemic on the life of higher education students, it was pertinent to delve into the academic and social life of higher education students from India. There are studies on the impact of Covid 19 on Indian students, but few studies have covered how the students perceive online education and how they are dealing with their social life. The present study covers the gap and adds to the literature by analyzing the impact of Covid 19 on college and university students using an online questionnaire.

The rationale for the study

The present study is an endeavor to explore the impact of Covid-19 on the academic and social life of the students from the colleges and universities of West Bengal. The study will add to the existing literature by comprehending the extent to which higher education students are coping with online classes and the support they are garnering from the institutions and teachers. Secondly, the social aspect of their lives will help them understand their social life in this pandemic and how they cope with subsequent isolation. Furthermore, the study was conducted on higher education students as previous research has shown that adults in the age group of 21 years and above are more concerned and worried about future job prospects and economic conditions, which adds to their stress (Ahmed et al., 2020; Huang & Zhao,2020). Knowing the areas where students have difficulties, teachers and institutes can devise a roadmap to deal with the present situation and similar situations if it arises in the future.

Objectives

The following objectives were investigated in the study:

a) Analyzing the impact of Covid 19 on the academic life of higher education students.

b) Determining the infrastructure facilities at home for the online classes.

c) Investigating the impact of Covid 19 on the social life of the higher education students.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 216 students from different colleges and universities of West Bengal (Table 1). There were 82% female and 18% male students. With respect to age groups, 20% were in the age group of 16 to 21 years, 73% were in the age group of 22 to 25 years, and 7% were in the age group of 26 to 35 years. 1% of the participants were from Doctoral background, 87% were pursuing a Master’s degree, and 13% were pursuing Bachelor’s degree. With respect to the field of study, 36% were from Arts and Humanities, 5% from Natural and Life Science, 2% from Applied Science, 2% from Commerce, and 55% from Social Sciences. All the participants had voluntarily consented to fill out the online questionnaire.

Instrumentation

The questionnaire used in the study was adapted from a questionnaire designed by Aristovnik et al. (2020) entitled “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students.” The online questionnaire was designed to collect data from higher education students worldwide. The present study adapted a questionnaire and included demographic information about the participants. It comprised questions on the impact of covid 19 on the academic life which had 12 questions, availability of infrastructure at home for online classes that comprised two questions, impact of covid 19 on the social life that had two questions, and emotional life which included one question and general life circumstances which had thirteen questions. The present study focuses on academic life, the availability of infrastructure at home, and the social life of higher education students. The data was collected through a google form.

Analysis

The collected data of 216 students were tabulated in excel sheets, and the percentage was calculated for each item in each question.

Results

Academic Life

The questions related to academic life covered the areas such as satisfaction with the organization of lectures during the pandemic, the dominant form of lectures, level of satisfaction of with online classes/lectures, dominant forms of online tutorials and seminars, different communication modes used by teachers and students, online supervisions, the preferred method of online supervision, provisions made by lecturers in online classes, the amount of workload, level of satisfaction with lectures and supervisions, satisfaction with teaching and administrative support, view on teaching-learning online.

Satisfaction with Organization

of lectures during Covid 19

As indicated in Table 2, 46% of the students were satisfied with the online presentations sent to the students, 45% of students were satisfied with the online video conference, and 43% showed satisfaction with written communication such as chat and forums. The percentage for “very satisfied” was low for all the forms of online classes. Special attention needs to be given to those students who were neutral in their response to organization of lectures. It could be that the colleges and universities they belong to do not have appropriate arrangements for online studies.

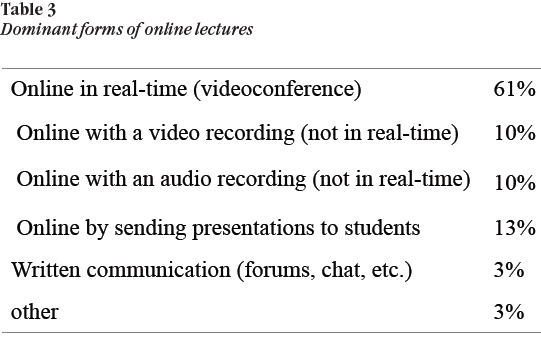

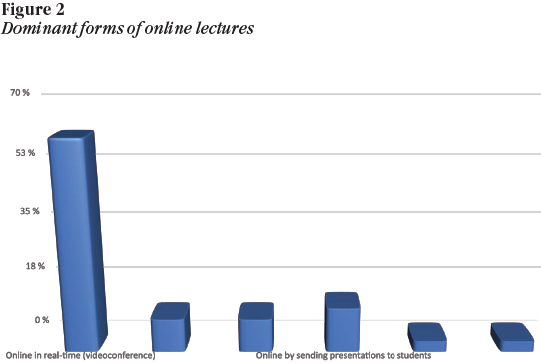

Dominant forms of

online lectures

The most dominant forms of online lectures revealed that a maximum of students (61%) used video conferences, online sending of presentations (13%), audio recording (10%), and video recording (10%). This indicates that most of the institutions followed the video conferencing mode for delivering lectures (Table 3; Figure 2)

Level of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with different forms of online

tutorials/seminars and practical classes

Table 4 and Figure 3 indicate the satisfaction level of the students with online lectures and tutorials. While 43% were satisfied with online video conferences, 19% remained neutral and only 11 % were very satisfied. For lectures with video recording, 33% were satisfied, and 18% were neutral, while 26% marked not applicable. 31% were satisfied with audio-recorded lectures, 17% were neutral, and 25% said it was not applicable to them. For online presentations, 43% of the students were satisfied, 15% were very satisfied, and 15% expressed a neutral position. For written communications, 37% were satisfied, 20% were neutral, and it was not applicable for 19%. While most of the students were satisfied with online teaching, tutorials, and seminars, some were dissatisfied, neutral and some wrote inapplicable. This indicates that either they had hurdles in attending classes and tutorials or they were not interested in online classes.

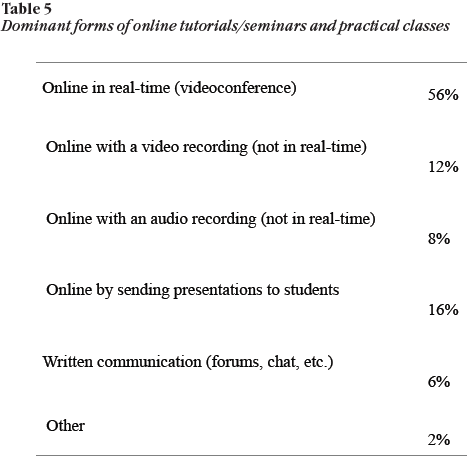

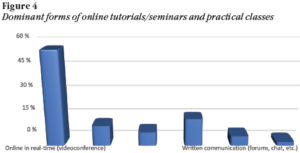

Dominant forms of online tutorials/seminars and practical classes

Similar to the response on dominant forms of lectures, maximum participants, i.e., 56%, reported that online tutorials, seminars, and practical classes were held through video conference, while 16% stated that tutorials and seminars were conducted by sending presentations online. 12% reported that video recordings were used for tutorials and seminars (Table 5; Figure 4)

Communication mode/modes used for online classes

Participants were asked to mention how they received teachers’/supervisors support after on-site classes were cancelled. Multiple answers were accepted to this question. It was found that 41% of participants received support through 1 type of communication, while 38% used 3 to 4 types of communication, namely video conference, video recording, audio recording, sending presentations, and written communications. 19% reported using two types of communication modes (Table 6; Figure 5). Only 2% of students stated they had no supervision. It was found that maximum students selected video calls, email communication, and social networks.

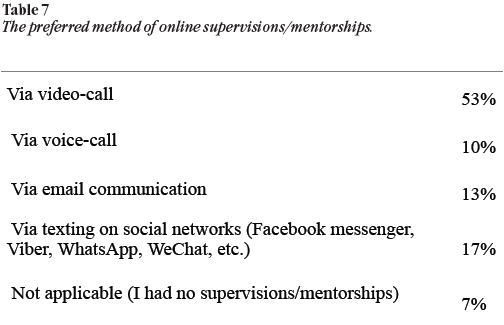

The preferred method of online supervision/mentorship

Table 7 indicates that the preferred method of online supervision was video call, with 53% of participants selecting the video call option. 17% of participants selected social networks (Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, WeChat), and 13% selected email communication. 7% had no provision of mentorship and supervision (Figure 6).

Provisions made by lecturers after the cancellation of on-site classes

49% of the participants agreed that lecturers provided them with assignments and homework regularly, 19% strongly agreed, and 17% were neutral about it. For feedback by lecturers on assignments, 44% agreed, 17% strongly agreed, and 23% held a neutral position. 48% agreed, and 21% strongly agreed that their queries were answered by teachers timely. 49% of the participants agreed, and 23% strongly agreed that lecturers were open to students’ suggestions and adjustments of online classes. 45% agreed, and 24% strongly agreed that they were informed about the examination pattern in the new situation, while 19% were neutral about it (Table 8, Figure 7).

Amount of workload

The participants were asked about the workload after the cancellation of on-site classes, and most of them, i.e., 29% stated that the workload was the same, 27% said it was smaller, and 15% said it was larger (Table 9, Figure 8).

Level of satisfaction with lectures and supervisions

Concerning lectures, 46% of students were satisfied, 17% were very satisfied, and 19% expressed a neutral position. 40% were satisfied with the tutorials/seminars and practical classes, 15% were satisfied, and 17% were neutral. Supervisions and mentorship were satisfactory for 38% of participants, very satisfactory for 14% of participants, 25% of the participants were neutral, and 12% declared it was not applicable in their situation (Table 10, Figure 9).

Satisfaction with teaching and administrative support

As far as teaching staff is concerned, 43% of the participants were satisfied, 16% were very satisfied, and 24% held a neutral position. 38% were satisfied with technical support, only 6% were very satisfied, and 30% were neutral. Concerning the students’ affairs office, 33% were satisfied, 30% were neutral, and 15% were not applicable. Regarding finance and accounting matters, 32% were satisfied, 28% were neutral, and 16% selected not applicable. Library public relations, 29% were satisfied, 25% were neutral, 17% were dissatisfied, and 15% marked not applicable, indicating library services were not appreciated. Statement on public relations (websites and social media information, showed that 40% of students were satisfied, 28% were neutral, 10% were very satisfied, and 10% of students stated it was not applicable to them. With the Tutors 37% were satisfied, while 26% were neutral, 14% selected not applicable. Concerning student counseling services, 32% of students were satisfied, 26% were neutral, 19% selected not applicable, and 9% were dissatisfied, and 6% were very dissatisfied (Table 11; Figure 10).

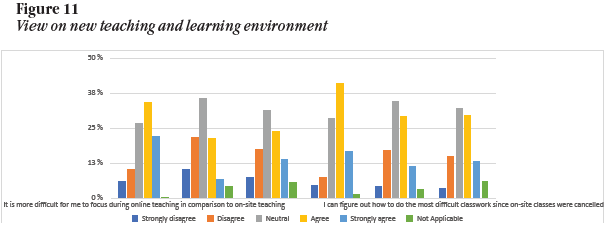

View on new teaching and learning environment

Participants were asked about their level of agreement with the teaching and learning environment whereby a mixed response was procured. Focusing on online teaching compared to on-site teaching was difficult for 34% of the students, and 22% strongly agreed, while 27% were neutral, and a small percentage disagreed (10%) and strongly disagreed. Regarding improvement in performance in online classes, 21% agreed, while 22% disagreed and 36% were neutral. Regarding performance deterioration, 24% of the students agreed, 18% disagreed, and 31% held a neutral stance. For adaptation to a new teaching-learning environment, 41% agreed, 17% strongly agreed, and 29% neutral. Mastering the skills taught in online classes, 29% of the participants agreed, 35% were neutral, 12% strongly agreed, and 17% disagreed. For being able to do the most difficult task in online classes, 30% of the participants agreed, 32% were neutral, 13% strongly agreed, and 15% disagreed (Table 12; Figure11).

Infrastructure and Skills for studying at Home

Two questions were asked regarding infrastructure at home for online studies and the computer skills of the students.

Access to infrastructure at home for online studies

Regarding infrastructure, 38% had a quiet place to study, while 30% sometimes had access to a quiet place. 38% of the participants had access to desks, and 25% never had a desk facility. 41% of the participants never had a computer with them, indicating their problems while doing assignments online. In comparison, 31% always had a computer, and 16% sometimes had access to a computer. 38% never had the required software and programs, 25% always had the necessary software and programs, and 18% sometimes had it. 73% never had a printer with them. Headphones and microphones were accessible for most of the students, with 63% stating that 63% always had headphones and microphones.49% of the students expressed that they did not have the facility of a webcam. In comparison, 24% always had access, and 12% sometimes had access to a webcam. 64% of the participants always had office supplies with them as it is the basic requirement which is easily available at reasonable rates. Only 10% of students said they never had office supplies. Regarding the internet connection, 31% always had an internet connection, while 26% said they often had an internet connection, and 27% said that sometimes they had internet. 35% of participants always had course study materials, 29% sometimes had access to course materials, and 18% often had course materials with them (Table 13, Figure 12).

Students’ opinions about their computer skills

46% of the participants knew how to browse information online, 22% strongly agreed that they knew how to browse, and 21% were neutral. 41% agreed, and 21% strongly agreed that they knew how to share digital content. 23% were neutral in this regard. Regarding knowledge about using online teaching platforms (Big Blue Button, Moodle), 40% agreed, 13% strongly agreed while 14% disagreed, and 27% were neutral. Using online collaboration platforms (zoom, skype), 47% agreed, 19% strongly agreed, and 22% were neutral. Regarding using online communication platforms (email, messaging), 53% agreed, 27% strongly agreed, and 15% were neutral. As for the software and programs required for studies, 40% agreed, and 13% strongly agreed that they knew to operate necessary software and programmes. 26% were neutral, and 14% disagreed. Regarding applying advanced settings in software and programs, 34% took a neutral position, 27% agreed, 10% strongly agreed, and 21% disagreed (Table 14; Figure 13).

Social skills Communication

The social dimension aims to understand the frequency of interaction of the participants

with the people around them.

Frequency of communication with people during a pandemic

Participants’ communication frequency with close family was good, with 30% stating that they spoke to the close family members several times a day and 19% stated that they spoke several times a week. 11% did not communicate with their family members, 13% spoke two or three times a month, and 13% spoke once a week. Maximum participants (31%) indicated that they were not in contact with distant family members, while 24% communicated two or three times a month and 22% spoke once a week. 19% spoke to close friends several times a day, 20% spoke two to three times a month, and 18% spoke once a week. 38% of the participants did not communicate with their roommates, while on the other spectrum, 26% spoke to roommates several times a day. Participants’ responses showed that 26% of them did not communicate with neighbors at all, while 20% communicated two or three times a month and 16% several times a day. 26% of participants never communicated with their colleagues from the course, and 20% communicated once a week. Regarding communication frequency with lecturers, 32% never communicated with lecturers, and 23% communicated two to three times a month. The frequency of communication with administrative staff and voluntary organizations was scarce. 68% of participants stated they did not communicate with the administrative staff and voluntary organizations. Communication with social networks was divided, with 26% stating that they never communicated with social networks and 26% stated they communicated several times a day. 56% of participants expressed that they never communicated with “someone else” during the pandemic (Table 15; Figure 14).

The closest person to confide in

Participants chose close family members when faced with a problem in covid times. 75% stated they would consult their family members if they fell sick, and 42% said they would turn to their family members if they felt depressed. In matters related to lectures and studies, 40% stressed that they would turn to their close friend. For future education, 42% said they would consult their family members. Regarding personal finances, 62% of participants said that they would turn to their family members. Regarding problems related to family and relationships, 48% said that they would consult their close family member, and 31% said a close friend. 50% of participants said they would consult their close family members on issues related to a professional career. Regarding covid 19 crisis, 51% of participants selected their close family friends while 21% selected their close friends (Table 16; Figure 15).

Discussion

Academic Life

The survey conducted in this study revealed that Covid 19 had impacted the academic life of some the higher education students. With a drastic change in the platforms used for the teaching-learning process, the dominant forms of online learning preferred by institutes and students were video conferencing, followed by online sending of presentations. The areas of students’ dissatisfaction were identified as follows: (a) While maximum students were satisfied with online video conferencing and online presentations sent to them, a sufficient percentage of students expressed a neutral position in this regard. (b) Students were satisfied with online seminars and tutorials. Yet, one cannot ignore a fair percentage of dissatisfied students and others who held a neutral position and those who found it inapplicable in their situation. This points out the lack of uniformity in universities and colleges regarding online seminars and tutorials so that some students did not experience the online seminars and tutorials. (c) Many students pointed out that they used one type of communication: video conference, while a good percentage used more than two types of communication modes. This shows the disparity in the facilities that students have while studying online. (d) Many agreed that provisions made by lecturers in online classes were good in terms of providing assignments, feedback, and being open to suggestions. Few percentages disagreed, strongly disagreed, and were neutral, indicating that their online classes did not include assignments and classes were not interactive. (e) Regarding workload, opinion was divided where some said it reduced and few found the workload to be large enough. (f) Students were satisfied with lectures, online supervision and tutorials, and practical classes. The percentage of “very satisfied” students was less, and a fair percentage of students were not satisfied with these online teaching procedures. (g) Regarding satisfaction with teaching and administrative support, many were neutral with regard to IT services, students’ affairs office, tutors, and students counselling services which indicates a lack of proper services from these support systems. (h) Many students agreed that it was difficult to pay attention in online classes. (i) Students were unsure whether their performance improved in online studies and therefore expressed a neutral position.

In similar studies conducted worldwide, mixed results were reported concerning the academic life of higher education students. As the universities and colleges varied in their platform of conducting classes and also giving assignments, the students had a different experience. For instance, Dutta (2020) found that students were satisfied with online classes and appreciated the teachers’ efforts. Similarly, learners in the study by Gonzalez et al. (2020) reported that Covid 19 situation had impacted their learning positively as they were able to enhance their learning. On the contrary, the Afghan students (Hashemi, 2021) stated that the covid situation negatively impacted their academic performance and revealed their dissatisfaction with online teaching. Even the undergraduate medical students in the study by Sharma et al. (2020) were dissatisfied with the online teaching. Practically online teaching cannot supplement the face-to-face interaction between teacher students. In on-site classes, the students understand the concepts better and interact better, and this was stressed by the university students from Mizoram in a study conducted by Mishra et al. (2020). The students in Mishra et al. (2020) study appreciated that education was continuing during the pandemic but found it difficult to attain conceptual clarity on all the topics. In the present study, some students showed satisfaction with online classes through video conferences and sending of recorded learning materials, but some students were dissatisfied and neutral about the effectiveness of online learning. This indicates that while the students who could attend the classes with all the facilities at their disposal may have found it convenient, those with restricted infrastructure and devices at home may have found it difficult to attend the classes regularly. Dissatisfaction also emerges when online teaching does not cater to the needs of the students, and they find it uninteresting. Undoubtedly, it is challenging to keep a class engaged in online teaching and provide feedback to all if there are many students (Pokhrel & Chhetri). In Indian classrooms, there are many students, and with online teaching and intermittent internet connections, it may not be easy to discuss and give feedback to every student.

Regarding workload, the student’s opinion in the present study was divided when asked about the workload with some accepting it has reduced, while few accepting it had increased. In a study by Yang et al. (2020), too much workload is positively associated with stress, leading to physical and mental health problems. Too many assignments and online work may not be possible for all the students, particularly those with limited infrastructure at home, which may lead to stress.

Infrastructure at home

Another area that was surveyed in this study was the availability of infrastructure at home and computer skills. Maximum students revealed that they had adequate computer skills, and many of them knew how to browse online, share digital content, and use software and programs. The present study showed that maximum students did not have a quiet place to study, and desks, computers, and webcams were not available for many of them. Some of the students reported that they never had the necessary software and programs. A good internet connection was not available at all times for many students. Even Dutta (2020) found that limited internet facilities and mobile data became a hurdle for students as after attending online classes the students were left with no data for assignments. Bania and Banerjee (2020) pointed out that lower socioeconomic backgrounds students face a problem in online studies due to a lack of infrastructure. Considering the fact that many parents had lost their jobs (Jha & Kumar, 2021) and the pandemic had led to financial constraints in many homes, not all students had the essential requirements for online classes.

Social life

Social interaction with people around is an essential aspect of mental and physical well-being. Due to the pandemic, many students were bereft of face-to-face interaction and communication. A decrease in social interaction impacts mental well-being with high-stress levels (Jiao et al., 2020; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). In a study, Saeri et al. (2018) concluded that social connectedness is a strong predictor of mental health. Elmer et al. (2020) conducted a study on students from Switzerland and found that lack of social interaction affects mental well-being. The present study found that students communicated with their close family quite frequently, and some interacted with their close friends. However, there were not many students who interacted with lecturers and administrative staff. While some took an interest in interacting on social media, others were not interested in social network interaction. When asked to select the person they would approach in the first instance when faced with any problem, the majority mentioned their closest family member, and the next option was their closest friends. Options of neighbors, social networks, lecturers, and administrative staff were not selected by many.

It cannot be denied that online classes helped fill the gap of interaction and allowed students to interact online in some way or the other (Alghamdi, 2020; Burns et al., 2020), but it was not the same as face-to-face interaction. In the present study, it was not known whether the online classes substituted the need of the students to interact with people, but it shows that most of them frequently interacted with close family and friends. They rarely or never interacted with teachers/lecturers and administrative staff. This implies the students were hesitant to talk about their studies or about problems in life with their teachers, and this area certainly needs improvement by the institutes.

Conclusion and Suggestions

To conclude, the present study highlighted that the pandemic had mixed effects on the academic and social life of the higher education students from different strata of the society and from the different colleges and universities of West Bengal. The study adds to the existing literature by presenting the students’ opinions on their academic and social life. The students‘ dissatisfaction and their neutral stand on some topics related to online education indicated that there is a lot to be done for the student community to improve their academic and social life. The results enlighten the teachers and administrators about a section of students who are not availing the benefits of online teaching-learning due to some hurdles in their lives. Moreover, the study points out the way interaction with teachers and administration is minimal and needs improvement.

The pandemic has taught the teacher and students community a new mode of teaching that was prevalent before but had never been used thoroughly. Higher education students are likely to be stressed about the future, and online teaching adds to their stress. While some students smoothly adjusted to their classes, many struggled with the lack of devices and internet issues. The universities’ administration needs to consider the plight of such students and offer solutions in some form so that they do not lose out on their education, for instance, providing free devices. Secondly, teachers should be trained in the post-covid situation to deal with online classes and they should be well equipped with the knowledge of various e-learning platforms. Teacher training programs need to include planning and execution of e-lesson so that future teachers can be prepared for such situations. Team teaching, discussion, and interactive strategies can motivate the students in online classes (Mishra et al., 2020). Also, there is a need to prioritize Open Educational Resources and open-source technologies, and they should be accessible to both teachers and students (UNESCO, 2020). Thirdly recording the lecture and making it available online, and taking tests from time to time may help those who have internet issues. Lastly, online counseling sessions and workshops can be arranged for a small group of students regularly to solve the problems faced by the students in personal and academic life.

Limitations of the Study

The present study had its shortcomings which can be overcome in future studies. The gender of the sample in this study was biased, with more female students than males. The sample was not a representative one in terms of the level of study, academic disciplines and age. Furthermore, the data collected was quantitative, so the researchers could not fully fathom the reasons for a particular choice of option. Future studies with an amalgamation of quantitative and qualitative design with a representative sample may yield insightful results. Furthermore, studies comparing rural and urban students will help explore the problems faced by the students in different areas.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Fundings: There was no funding to conduct the study.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to express their gratitude to Mr. Aleksander Aristovnik for permitting us to use the tool he developed with his co-authors. The present study was inspired by the original study conducted by *Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020).

The authors would like to thank the participants of the study who voluntarily took part in the study and shared their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Aboagye, E.; Yawson, J.A.; Appiah, K.N. COVID-19 and E-Learning: The Challenges of Students in Tertiary Institutions. Soc. Educ. Res. 2020, 1–8.

Agoramoorthy, G. (2021). India’s outburst of online classes during COVID-19 impacts the mental health of students. Current Psychology, 1-2.

Ahmed, M. Z., Ahmed, O., Aibao, Z., Hanbin, S., Siyu, L., & Ahmad, A. (2020). Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian journal of psychiatry, 51, 102092.

Alghamdi, A. A. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social and educational aspects of Saudi university students’ lives. Plos one, 16(4), e0250026.

*Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438.

Bania, J., & Banerjee, I. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Higher Education: A Critical Review. Higher Education after the COVID-19 crisis.

Bao, W. (2020). COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: A case study of Peking University. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(2), 113-115.

Burns, D., Dagnall, N., & Holt, M. (2020, October).

Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student well-being at universities in the United Kingdom: A conceptual analysis. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 5, p. 204). Frontiers.

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry research, 287, 112934.

Chakraborty, P., Mittal, P., Gupta, M. S., Yadav, S., & Arora, A. (2021). Opinion of students on online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(3), 357-365.

Chandasiri, O. (2020). The COVID-19: impact on education. Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities, 6(2), 38-42.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Malik, K., Gellatly, R., Boustani, M. M., Michelson, D., Knudsen, K., Mathur, S., & Patel, V. H. (2020). Design process and protocol description for a multi-problem mental health intervention within a stepped care approach for adolescents in India. Behavioral Research Theraphy, 133, 103698.

Coman, C., Țîru, L. G., Meseșan-Schmitz, L., Stanciu, C., & Bularca, M. C. (2020). Online teaching and learning in higher education during the coronavirus pandemic: students’ perspective. Sustainability, 12(24), 10367

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5-22.

Dreesen, T., Akseer, S., Brossard, M., Dewan, P., Giraldo, J. P., Kamei, A., … & Ortiz, J. S. (2020). Promising practices for equitable remote learning: Emerging lessons from COVID-19 education responses in 127 countries.

Dutta, A. (2020). Impact of digital social media on Indian higher education: alternative approaches of online learning during Covid-19 pandemic crisis. International journal of scientific and research publications, 10(5), 604-611.

Edjah, K., Ankomah, F., Domey, E., & Laryea, J. E. (2020). Stress and its impact on academic and social life of undergraduate university students in Ghana: A structural equation modeling approach. Open Education Studies, 2(1), 37-44.

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. Plos one, 15(7), e0236337.

Gonzalez, T., De La Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., & Sacha, G. M. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PloS one, 15(10), e0239490.

Hashemi, A. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 on the academic performance of Afghan students’ and their level of satisfaction with online teaching. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 8(1), 1933684.

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry research, 288, 112954.

Islam, M. A., Barna, S. D., Raihan, H., Khan, M. N. A., & Hossain, M. T. (2020). Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A web-based cross-sectional survey. PloS one, 15(8), e0238162.

Jha, P., & Kumar, M. (2020). Labour in India and the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Indian Economic Journal, 68(3), 417-437.

Jiao, W. Y., Wang, L. N., Liu, J., Fang, S. F., Jiao, F. Y., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., & Somekh, E. (2020). Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. The Journal of pediatrics, 221, 264.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban health, 78(3), 458-467.

Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100012.

Muthuprasad, T., Aiswarya, S., Aditya, K. S., & Jha, G. K. (2021). Students’ perception and preference for online education in India during COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), 100101.

Nash, C. (2020). Report on digital literacy in academic meetings during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. Challenges, 11(2), 20.

Nelson, B. W., Pettitt, A., Flannery, J. E., & Allen, N. B. (2020). Rapid assessment of psychological and epidemiological correlates of COVID-19 concern, financial strain, and health-related behavior change in a large online sample. PLoS One, 15(11), e0241990.

Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., & Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 104-112.

Pokhrel, S., & Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 133-141.

Qamar, T. Q., & Bawany, N. Z. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on Higher Education in Pakistan: An Exploratory Study. IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (15), 503-518.

Radu, M. C., Schnakovszky, C., Herghelegiu, E., Ciubotariu, V. A., & Cristea, I. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of educational process: A student survey. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(21), 7770.

Ranta, M., Silinskas, G., & Wilska, T. A. (2020). Young adults’ personal concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic in Finland: an issue for social concern. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy.pp1209-1219

Right to Education, 2014. https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to education.org/files/resourceattachments/RTE_International_Instruments_Right_to_Education_2014.pdf

Saeri, A. K., Cruwys, T., Barlow, F. K., Stronge, S., & Sibley, C. G. (2018). Social connectedness improves public mental health: Investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 365-374

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., … & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and health, 16(1), 1-11.

Sharma, K., Deo, G., Timalsina, S., Joshi, A., Shrestha, N., & Neupane, H. C. (2020). Online learning in the face of COVID-19 pandemic: Assessment of students’ satisfaction at Chitwan medical college of Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal, 18(2), 40-47.

Sheikh, Y. A. (2017). Higher education in India: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(1), 39-42.

Singh, S., Roy, M. D., Sinha, C. P. T. M. K., Parveen, C. P. T. M. S., Sharma, C. P. T. G., & Joshi, C. P. T. G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry research, 113429.

Suresh, M.; Priya, V.V.; Gayathri, R. Effect of e-learning on academic performance of undergraduate students. Drug Invent. Today 2018, 10, 1797–1800.

United Nations (2020). Policy Brief: Education during Covid 19 and beyond. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wpcontent/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf

UNICEF (2021) https://www.unicef.org/india/press-releases/covid-19-schools-more-168-million-children-globally-have-been-completely-closed

UNESCO Universities Tackle the Impact of COVID-19 on Disadvantaged Students. (2020). Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/news/universities-tackle-impact-covid-19-disadvantaged-students (accessed May 24, 2020).

UNESCO (2020) Education in a Post-Covid World: Nine ideas for Public action. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/news/education-post-covid-world-nine-ideas-public-action

Wang, C., & Zhao, H. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety in Chinese university students. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1168.

Yang, C., Chen, A., & Chen, Y. (2021). College students’ stress and health in the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of academic workload, separation from school, and fears of contagion. PloS one, 16(2), e0246676.

Yikealo, D., Tareke, W., & Karvinen, I. (2018). The level of stress among college students: A case in the college of education, Eritrea Institute of Technology. Open Science Journal, 3(4).

Santoshi Halder:

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6967-5853

All correspondence for this chapter should be made to

Santoshi Halder.

Email: santoshi_halder@yahoo.com shedu@caluniv.ac.in