Prof. Xavier Diez

Unió Sindical dels Treballadors d’Ensenyament de Catalunya – USTEC·STEs (IAC)

We often forget how emerged the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the United Nations system. As a historian, it is my responsibility to remind it. After the World War II, in the face of the brutal drama experienced by most of the countries, it was considered necessary to update the failed system of the League of Nations. And there comes Eleanor Roosevelt, the widow of the president of the United States who, a few weeks after the death of her husband, was designated as a delegate to the General Assembly of the United Nations, and a few months later, president of the Human Rights Committee that would be in charge of drafting the UDHR, finally presented on December 10, 1948. Eleanor, with her profound sense of humanitarianism, is widely recognized as the mother of the principles, values and architecture of the United Nations system.

Beyond this little encyclopedic information, it would be interesting to dwell on a few details. The UDHR is not only a response to the trauma of the World War II, the Holocaust, the horrible crimes against humanity of a dark period that would include the period beginning in 1914 when the supposedly civilized world decided to start a kind of „30-year war“ based on armed conflicts, genocides and totalitarianisms, but also the collapse of the economy that, starting in 1929, placed the majority of the world’s population in a situation of economic crisis and humanitarian chaos. The memory of misery, and how misery nurtured the resentment translated into the emergence of totalitarianism, implied that it was necessary to break with this dynamic and enter a new era of universal peace and prosperity. Then of course there was the issue of decolonization – in fact, the years following the UDHR saw complex and often violent processes of colonial independence and emancipation, especially in Africa and Asia.

How to ensure peace, prosperity and social justice? Education seemed to be the most direct instrument. This is why it occupies an outstanding place in the Declaration. Those men and women who decided to enter into global governance, inspired by the progressive spirit of the New Deal, thought that the best way to build a true United Nations in a state of economic convergence and social harmony was through the education of the younger generation. In this sense, this chapter expresses the trust in the progress of society through education, an idea shared by the various socialist and republican schools of the XIX and XX centuries. This is why education is an individual right, but, above all, a collective, national and global right. It was meant to improve personal conditions, but also to enable the desired economic development of nations -especially those that emerged after 1948- and to create a much more egalitarian and, therefore, peaceful world.

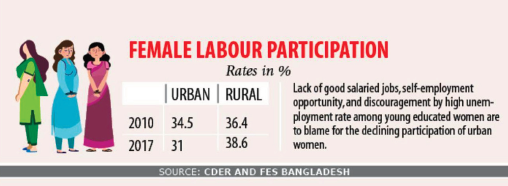

This first phase of optimism was relatively short-lived. Conflicts arising from decolonization and the Cold War failed to fulfil the hopes of the Declaration’s drafters. Although the majority of the former colonies achieved independence, this often turned out to be only superficial, as unequal relations of dependence persisted. Furthermore, public welfare policies were gradually weakened as the communist bloc became weaker and weaker. In many new nations, it was extremely difficult to fulfil the promises of development. The worst was yet to come. Starting from the 1970s, some of the UN institutions turned towards neo-liberal conceptions. The OECD, the successor to the government agency dedicated to administer the Marshall Plan, soon became a lobby for major multinational corporations that pressured the nations it assisted to take decisions contrary to their interests. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank started to put pressure on foreign currency lenders to cut public spending and open their economies to liberalization that was harmful to them. Education was one of the most affected areas. Many nations were forced to privatize their public systems, to cut funding, to stop paying teachers, to close schools. Whenever a country resisted, the US Secretary of State promoted military coups, such as those that took place in Chile (1973) or Argentina (1976), which resulted, especially in the first case, in the total privatization of its education system, as Naomi Klein explains in her book The Shock Doctrine. All in all, the last three decades of the twentieth century were catastrophic for so-called „developing“ societies. The new educational policies consisted basically of making teachers less functional (making their profession more and more precarious, worse paid and discredited), deregulating curriculums, decentralizing the system, granting economic and pedagogical autonomy to schools and initiating a system of educational segregation that continues and breaks with the original sense of making schools a space for equal opportunities. Naturally, there are important differences between different realities. Some Asian countries, which achieved high levels of industrial development and economic growth, managed to achieve certain levels of political independence and improved their education systems. Meanwhile, in general terms, regions such as Latin America and Africa, handicapped by the economic inequalities caused by globalization, have not been able to achieve sufficiently mature and effective systems to promote greater well-being.

And we arrive at a time marked by what Karl Schawb has called the „Fourth Industrial Revolution“, featuring the internet of things, intensive digitalization and artificial intelligence. While all these innovations are exciting, they also come at the cost of major uncertainties about the future of work and ensure a concentration of power and wealth in the hands of minorities and hence new, large inequalities, perhaps with the difference that it will particularly affect the developed world. It is precisely this new economic agenda that sets the scene for a number of educational changes. We are witnessing this from educational digitalization, with the increasing use of electronic devices, with the growing temptation of distance learning (and we have had the recent experience of the pandemic, with quite catastrophic results), but also through what they call educational innovation marked by a competency-based approach. This practically means downgrading curricular levels, gearing educational action towards the changing needs of an increasingly precarious and narrow labor market, and a great effort -in the sense of social engineering- to turn the pupil into a flexible individual, adaptable to the mutations of the economy, with few critical capacities, and with a great ability for resignation (disguised under the term „resilience“). Thus, essential elements such as the humanities or pure sciences seem to be an endangered species in schools and colleges. However, we also witness a growing autonomy of schools, both in terms of management and curriculum, which leads us to a segregated school, in which students are classified into social classes and which could take us back to a social structure of a class nature, such as the one experienced in the West before the French Revolution.

And here, especially among developed countries, we see a number of overlapping phenomena. First of all, as a commitment of the European Union, in order to achieve the objective of having 90% of students between 16- 18 years of age enrolled in post-compulsory studies, the graduation rate has increased, in such a way that we have gone from worrying percentages of educational failure to an (almost) universal promotion. And the latter is consistent with the fact that there has been a decrease in the educational levels of students since the year 2000. This is a process yet to be analyzed and to guess its causes, even though the perception is that digitalization has a high share of responsibility. However, the progressive loss of the humanities in the school curriculum, as well as unproven educational innovation approaches that imply a progressive lack of attention on the part of students, probably have a lot to do with it. In any event, it is clear that global educational policies, very much marked by the Sustainable Development Goals (also known as Agenda 2030) are likely to be successful in statistics, yet negative effects with respect to the hopes of the men and women who drafted, discussed and approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its Article 26.

* This article is published simultaneously in the 10th issues of PoliTeknik International and PoliTeknik Español