Peoples Education for Peoples Power:

Democratising the Education Clauses of

Universal Declaration of Human Rights and

Advancing the Transformation of

Education and Training in South Africa

Context Setting

The African National Congress (ANC) adopted a resolution on ‘Native Education’ at its annual conference of 1924 which urged the Union of South Africa (at the time, a self-governing dominion in the British Empire) to “… introduce legislative measures providing for the introduction of a free, compulsory, and public system of Native education” for the whole country. Twelve years later, the colonial regime instituted a review of education for the indigenous peoples of south Africa and found that “The ratio of the per capita expenditure on Whites compared to Blacks was 40:1 at that time” in 1936 (The Inter-Departmental Committee on Education for Natives). No Black person was represented on the Committee.

A further twelve-years after then, the National Party won the white minority elections in South Africa and set about implementing its odious policies of Apartheid (which would be designated a crime against humanity in 1973 based its definition as “inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them” (UN, 1973, International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid) in 1948. In that same year, the third session of the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted Resolution 217 (International Bill of Human Rights: Universal Declaration of Human Rights) on the 10th of December 1948.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights contains Article 26 which states that: “(1) Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit; (2) Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace; and (3) Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children” (UN, 1948).

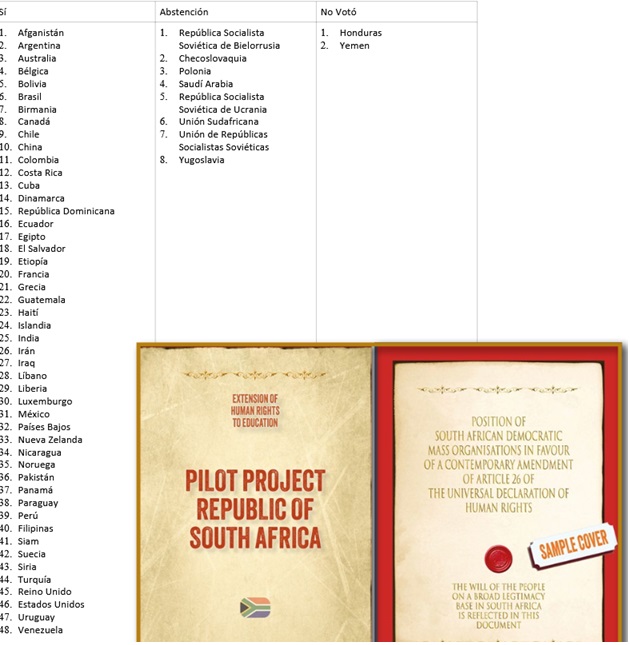

Around the time of the adoption of the International Bill of Human Rights, the world population was estimated to comprise of approximately 2.5 billion people (1950). The UN was constituted by 58 member states, and 83 % voted in favour, eight abstained, and two did not caste any vote (cf. Appendix 1) for the Human Rights Declaration. Seventy-six years later, UN’ General Assembly closed its 79 th session at the end of September 2024. With a world population currently estimated to exceed 8.2 billion people, the UN currently comprises of 193 full member States whilst the Vatican and Palestine1occupy non-member observer State status, and Western Sahara remains under colonial occupation as a Non-Self-Governing Territory.

The erstwhile Union of South Africa whilst remaining a ‘self-governing’ dominion of the British Empire until 1961, abstained from supporting the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The apartheid regime began rather systematising and institutionalising racial capitalism under an abhorrent and repugnant policy of Grand Apartheid. The apartheid regime established a Commission on Native Education in 1949. This did not include any Black people either. Some have argued that the Commission “… essentially laid out the philosophical and organisational foundations for the much of the affronting 1953 Bantu Education Act”.

The policy of Apartheid was deemed a crime against humanity by the UN in 19662. The General Assembly of the UN also adopted the Apartheid Convention that not only declared that apartheid was unlawful because it violated the Charter of the United Nations, but also that apartheid itself was criminal on the 30th of November 1973. Resistance to the imposition, maintenance, and reproduction of apartheid and struggles against racial capitalism continued to grow and gain further support both internally and internationally. In 1971, workers who were mainly recruited in the illegally occupied territory of Namibia embarked upon strike action on the mines. In January 19733, over 2,000 Black workers withdrew their labour from Coronation Bricks Work in Durban thereby kicking off what it is now generally agreed as the re-emergence of a militant and radical Black Trade Union movement. Other territories in southern Africa were advancing their national liberation struggles as both Angola and Mozambique freed themselves from the yoke of colonial bondage.

Bricks Work in Durban thereby kicking off what it is now generally agreed as the re-emergence of a militant and radical Black Trade Union movement. Other territories in southern Africa were advancing their national liberation struggles as both Angola and Mozambique freed themselves from the yoke of colonial bondage.

The apartheid regime subsequently invaded Angola and became a proxy agent for the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in its ‘cold war’ against the democratic socialist bloc represented by Cuba and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (who also supported the national liberation movements of South Africa). The apartheid regime was also seeking to further entrench its subjugation of the Black majority through imposing the main language of oppression (Afrikaans) upon the already limited and constrained public education and training curriculum. The youth of the country and especially the students of the Soweto (South Western Townships) heroically resisted and opposed the actions of the apartheid regime.

Primary and high school students with mobilisation and support from the community, liberation organisations, and the South African Students Movement (SASM) formed the Soweto Students Representative Council (SSRC) and began boycotting Afrikaans medium classes. On the 16 th of June 1976, the SSRC converged on Orlando Stadium in a peaceful demonstration but were confronted by a brutally violent response from the Apartheid Regime. Hector Peterson would by martyred on that day, and it is estimated that a further 1,000 people would be massacred by the Apartheid Regime. The terrain of learning and teaching became a core avenue in contesting the power of an illegitimate State whilst demanding the right to high-quality and free universal education and training for all. Further struggles would escalate and included the recognition of the value of education and training as a critical resource for lifelong learning and its utility as a global public good and service.

Forty-nine years later, and the public provision of education and training as a means of intergenerational informaion transfers drawing upon the global knowledge commons is under extreme pressure. Neoliberal forces ensconced amongst right-wing libertarian agents and neo-fascist populist regimes have gained significant ascendency within latestage capitalism in world systems. The contradictions between education and training system under duress of austerity and even being delinked from both contemporary productive capabilities in labour processes and deteriorating material conditions of the world majority are again vividly apparent. The advent of scholacide and scholasticide in west Asia as an auxiliary tool of genocide reflects the latest incarnation of crimes against education, educators, and scholars.

The advent of scholacide and scholasticide in west Asia as an auxiliary tool of genocide reflects the latest incarnation of crimes against education, educators, and scholars.

It is within this context of resistance, contestation, and global struggles against ecological precarities that the Call for Papers to a conference to discuss and strategize about updating the education clauses of the Human Rights Charter of the United Nations to reflect our current realities. Towards ensuring a vibrant and empirically informed engagement amongst progressive forces, this conference also seeks to pay attention to the education and training reforms effected since the democratic breakthrough of 1994 and to assess the impacts and outcomes generated across three decades. The challenge for transformation would then be properly located within history and also offer insights and learning from struggles across the planet.

Scientific Committee drawn from the Advisory Council of the RSA-Pilot Team will ensure that academic relevance and integrity is maintained. A local organising group will work on resourcing and logistical arrangements.

Whilst it is expected that the conference will be convened in August/September 2025. The deadline for Papers is End of July 2025. More details on funding, timelines and resulting publications will be made available in the near future.

Annexure 1: United Nations General Assembly Voting Summary (1950)

- 146 of the 193 UN member states (76%)

recognise Palestine as a sovereign state as of June 2024. - Resolution 2202 A (XXI) of 16 December 1966.

- 91 votes in favour, four against (Portugal, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States) and 26 abstentions. By 2008, 107 member States ratified the Apartheid Convention.