Bülent KAYA

Political Scientist – SWITZERLAND

picture: Created with AI

Judging Donald Trump’s overall political behavior and the numerous economic and political decisions he has made since the beginning of his second term, his governing style might be described diplomatically as “individualistic and unpredictable,” or more harshly as “absurd and insane.” This appreciation is not incorrect entirely, but it is incomplete. Unlike what it seems, behind Trump’s behavior lies a more systematic and deeper philosophical perspective and ideological model.

Trump is consciously implementing a decision-making model based on personal intuition, loyalty relationships and direct execution, rejecting traditional political rules and the stability of institutional structures. In its basic outlines, this model is based on an intellectual foundation that prioritizes efficiency, orientation to results and attempts to reduce the institutional operation of the State to the management approach of a company. Thus, we should make an effort to understand Trump’s noisy announcement to impose tariffs against many countries not in terms of his personal obsession, but in terms of his conflicting vision of the world, his understanding of the need for the state to show strength in international trade and, above all, in terms of basic intellectual concepts such as a doctrine of statesmanship based on the leader’s efficiency and ability to do business.

What are the main conceptual outlines that shape Trump’s intellectual orientations and actions? This article, by addressing this question, aims to contribute to efforts to interpret Trump’s decisions in a more systematic way.

State management in political philosophy and public administration: Efficiency or legitimacy?

The question of who should govern the state and how the state should be governed is one of the oldest and most polemical questions in human history. If we look at the history of debates in the fields of political philosophy and public administration, we can say that they revolve around two main questions: Is the state’s legitimacy or its efficiency and effectiveness the priority? This question has obsessed not only academic circles, but also the minds of administrators, political philosophers and citizens throughout the ages.

These debates, which have been going on since ancient Greece, have profoundly marked the history of thought. Plato’s idea of the “Philosopher king” can be considered the ancestor of the way of understanding government that today we call technocracy. Aristotle, for his part, emphasized both the moral and functional aspects of government, classifying political regimes not only in terms of the balance of power, but also in terms of the amount of virtue or corruption.

Machiavelli is considered among the first modern thinkers who addressed the question of governmental efficiency with his book The Prince. The ideas contained in this book focus primarily on how a ruler can maintain and consolidate his power. According to Machiavelli, a determined and all-powerful ruler can overcome all problems faced.

Subsequently, thinkers such as Hobbes and Locke addressed this debate with the concept of the social contract. While Hobbes argued the need for a strong central authority to avoid chaos, Locke pointed to the importance of individual liberties and representative democracy. Marx, in his turn, shook up the issue radically, defining the state as an instrument of oppression that protects the interests of the ruling class and argued that legitimacy does not come from the people, but from those who own the means of production. Max Weber, for his part, systematized this intellectual legacy and presented a more analytical framework that based legitimacy on different sources such as charisma, tradition and law.

Since the 1980s, neoliberal thought has appeared on the scene. This approach, which aims to reduce the size of the State, introduce market logic into public administration and bless efficiency, has installed a strong hegemony not only in academic circles, but also in the minds of politicians and in actual practices. In recent years, however, a new stream of thought has begun to emerge that questions this dominant paradigm and adopts harsher and more radical tones: The Neoreaction. Beginning in the 2010s, this movement started to make its presence felt especially in technological circles and alternative thinking platforms, raising radical but effective questions about how the state should be governed.

Critique of Democracy by Curtis Yarvin, the behind-the-scenes ideologue of Neoreaction and Trumpism

Curtis Yarvin is an extraordinary figure who has made a sharp turn from the tech world into political philosophy. Yarvin, who has a background in software engineering, has earned many followers in the dark corners of the Internet as the 2010s approached with his blog posts written under the pseudonym “Mencius Moldbug.” Over time, he became not only a writer, but also the father of a radical idea known as „neoreaction“. To describe him as a classical conservative would be quite insufficient, since Yarvin’s target is modern democracy itself.

In Yarvin’s world of thinking, democracy is a slow, ineffective and often dysfunctional system. According to him, today’s democracies produce not only a form of government, but also an ideological structure that shapes society and imposes a single type of thinking. He calls this structure the „Cathedral“. According to this metaphor, institutions such as major media outlets like the New York Times, famous universities like Harvard, the judiciary and the bureaucracy are seemingly impartial propaganda tools, but in reality they inject liberal ideology into every corner of society. These institutions do not represent the interests of the people; on the contrary, they exercise power to maintain their ideological order. In this respect, the hegemony emphasized by the metaphor of the “Cathedral” resembles Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony, but in Yarvin’s view, this “Cathedral” system has a much more homogeneous, organized and oppressive character.

The solution Yarvin proposes is very unorthodox: Run the State as a private enterprise. In his view, a successful state should be managed like a company, with a strong CEO, whose decisions are quick and direct. He prefers an oligarchic management model made up of large capital owners who come into office on merit, rather than elected leaders. Instead of systems based on broad public participation, the emphasis should be on effective decisions made by competent managers. In short, at the forefront is management effectiveness, not the ballot box.

This perspective stresses that a good leader should not be constantly accountable to the people, but should produce successes with the decisions he makes. In Yarvin’s view, the head of state (the president) should focus on results-oriented governance, not on popularity contests. For this reason, his model resembles the culture of modern startups: take risks, make quick decisions and continuously measure results. In summary, for Yarvin the important thing is not democracy, but a functioning system of government, because in his opinion the supposed will of the people is often just a pleasant illusion.

Trumpism and Neoreaction: Corporatization of the State

Trump’s presidential term shook not only political traditions, but also the concept of governance. The interesting thing is that his unconventional style is very similar to the “CEO-state” model that Curtis Yarvin theorized long time ago. Trump’s view of the state as a corporation, his loyalty-based appointments, and his view of bureaucracy as an obstacle to conducting business are almost identical to Yarvin’s idea that “government must work efficiently and decisions must be made quickly.” The initiatives undertaken by Trump to trim the powers of institutions such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the State Department are exactly the practical application of this approach. Such similarities are not only structural, they also manifest themselves in times of crisis. Rather than listening to experts, Trump created his own circle of advisors and ignored the opinions of federal agencies. For instance, his quarrels with White House health advisor Anthony Fauci on the pandemic point to an approach to governance in which it is the leader’s charisma, not his or her expertise, that is decisive.

Trump’s speech, which refused to accept the results of the election he lost and paved the way for the events of Jan. 6, seemed to put Yarvin’s criticisms of democracy into practice. While Yarvin argued that the system based on popular vote was irrational and that decisions should be made by competent people, Trump had the mindset of “I have been elected, but not because I have the people’s legitimation, but because I am just.” This was a conception of politics based on personal leadership, not institutions, and a striking parallel to Yarvin’s model of a rational, hierarchical government free from the direct influence of the people.

With Trump’s reelection in early 2025, the “Ministry of Government Efficiency,” led by Elon Musk, initiated a massive decimation of the federal bureaucracy, and more than 100,000 public employees were laid off. The Ministries of Housing and Urban Development and Education suffered the most; such radical purges are still the subject of uncertain legal proceedings. The government also decided to cut billions of dollars in funding for health and research projects. It is possible to interpret all these steps as concrete responses to the idea of eliminating the heavy bureaucratic structure and managing the state with a more “efficient” corporate logic, as defended by Yarvin.

Similar traces can be seen in economic and technological policies. Trump’s direct State intervention by ignoring free market rules with tariffs is very reminiscent of Yarvin’s dream of a State acting as a CEO. Moreover, that private sector leaders such as Elon Musk play an active role in state projects and the prominence of individuals deemed “successful and smart” rather than elected politicians are consistent with Yarvin’s view that oligarchic elites should be directly involved in governance. In sum, although Trump has not kept Yarvin’s books by his bedside, his practices seem to epitomize these ideas. Curtis Yarvin serves as Trump’s de facto behind-the-scenes ideologue.

Trump is a symptom…

Trump’s decisions and approaches are often explained as incoherent, insane or populist. However, such interpretations limit themselves to observing the waves on the surface, while ignoring the deeper currents. All in all, perhaps the most fruitful way to understand Trump’s practices is to view them not as individual deviations, but as symptoms of an ideological transformation driven by figures like Curtis Yarvin.

The “CEO-State” model that Yarvin advocated at the theoretical level has been and is about to be put to the test under Trump in action: the dismantling of bureaucratic institutions, the centralization of decisions, the assumption of an oligarchic political role by technocrats and the wealthiest in business, etc. None of this is accidental. On the contrary, they are real tests of an alternative model of governance (Neoreaction), based on the widespread discontent that liberal democracy is “too slow, too disorganized.”

Trump may not have formulated these ideas theoretically, but his practice has opened up space for Yarvin’s neoreactionary vision on the ground. So, the question is not how “crazy,” “short-sighted,” or “absurd” Trump is as a leader. The question is what political aspirations and historical trends his practices reflect. Yarvin’s idea introduces a political imagination that emphasizes an oligarchic structure made up of appointed elites instead of elected representatives, efficiency instead of the common good, and hierarchy instead of pluralism. And Trump has become the crudest, but also the most visible, face of this imaginary. But he may not be the last. Who knows how many others are waiting out there to do the same?

At this point, it is necessary to stop and seriously question the concept of „efficiency“. What does efficiency mean? For whom, for what? For example, is it possible an economic success in a system governed by an oligarchic structure of billionaires? Let’s say yes — but what exactly does this success mean?

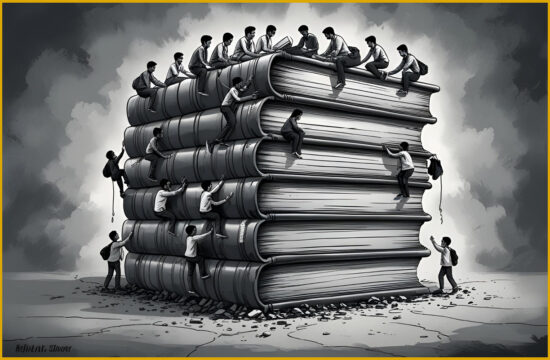

Let’s think about it: There is no functioning social system and no proper educational structures and institutions. But there is a leader who proclaims himself „successful in the economy.“ Is this the ideal state we want? Are we really talking about a success that benefits all layers of society, or will it be a system that only favors a handful of billionaire oligarchs? Another concept on which we should think about is the following: Continuity. In other words, how long can a state model that focuses only on economic performance survive in the long term? A management approach that ignores everything other than economic indicators to what degree can be sustainable?

I would like to end this article with another question: Is Yarvin’s „post-democratic“ vision a marginal idea or is it a new political reality into which we are being drawn step by step? If the latter is true, the question should not focus solely on criticizing Trump. The real question is how we can build a democratic line of defense against this administration.