Prof. Dr. Georg Auernheimer

A dam was built in the Hasankeyf valley to retain the water of the Tigris river, despite all international protests. As a result, settlements hundreds of years old are going to be under water. 10,000 people have lost their homes.1 This is a shameful dispossession with an obvious character. Nevertheless, dispossessions shaped the preliminary period and the history of capitalism. But today they are more subtle and concealed.

In post-war West Germany, when I was young, the world still appeared to be on the right track. It seemed that everyone was satisfied with the system. Talking about exploitation was „old-fashioned“. The average level of income, although modest, was sufficient to ensure a family’s living standard. Moreover, there was some security for old age and sickness, since in that capitalism there were still traces of a society based on solidarity. In terms of the exploitation of labor, it was no softer than in ancient times. The surplus value generated by the workers was reinvested by the companies, and this was the cause of the so-called „economic miracle“. A portion of this surplus value was transferred to the public institutions providing for general social interests, material and social infrastructure through the flow to the state in the form of taxes: Transportation, water and energy, educational institutions, social services. Back then, the poverty of citizens was something that no one knew about. People were content with territorial and social mobility. Also, in line with this, there was expectations of upward mobility in society, a belief in development, a sense of freedom and confidence.

This version of capitalism was based on historical reasons, confronted with the socialist system of the East, which required the process of reconstruction, which required more workers and more reserve investments, and caused the equalization of social standards. In the USA, the first stage of Fordism and the accumulation regime of the New Deal policy of the 1930s were in the same specific historical situation, in which it was necessary to add sufficient purchasing power to the market to ensure the realization of surplus value. On top of this, there was public investment in infrastructure. Both of these provided strong legitimacy to the system. In the USA as well as in Western Europe, capitalism was felt and lived as a normality. But still, Marx claimed the following: With the progress of capitalist production, there is formed a working class that accepts the demands of that production mode as a law of nature as a result of education, tradition and custom (MEW 23, 765).

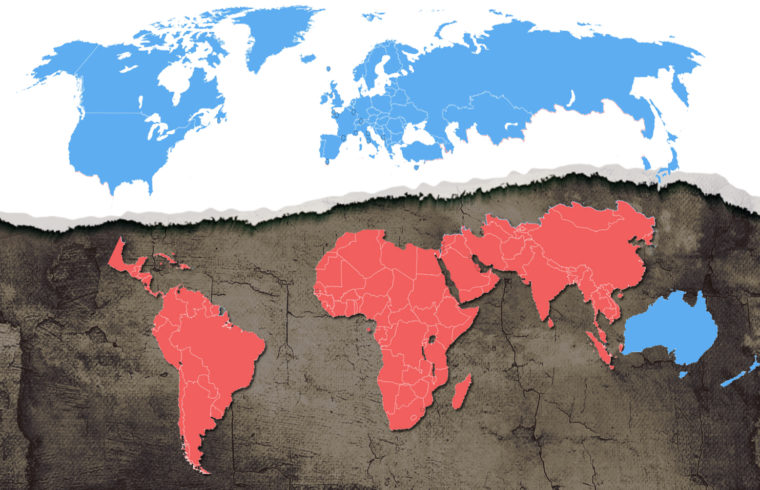

The people of the countries of the Global South experienced another type of capitalism, at least in Africa, and in a slightly more moderate form in Latin America. Their natural wealth, consisting of raw materials and agricultural products, is still being exported after their independence, as in the period of the colonial system. Moreover, the surplus value generated has been reinvested at a very low level up to now, and therefore no significant productive power is generated. We must add the transfer of profits abroad, especially when many foreign enterprises do so and also benefit from tax exemptions. As a consequence, resources for construction, infrastructure and public services are lacking. The State becomes impoverished and is constantly re-indebted. Not only are people exploited, as they do not create surplus value by working, but, unlike “ Rheinstyle Capitalism „, all surplus value is stolen outside the production process. The infrastructure remains weak and the state abandons the people to their fate. By means of expropriation, the relation of exploitation is extended.

Expropriation is to be distinguished from exploitation, from the retention of the surplus value that workers create in the production process (see: Harvey 2015, 75). In contrast to exploitation it is not a direct part of the capital relation, it completes the extended reproduction of capital. Whitfield (2020) refers to Harvey’s concept of „dispossession“, Foster/Clark (2020) describes these process as „expropriation“ or „robbery“.

This situation, which may be clarified in the peripheral countries, is becoming an increasing reality in the central countries due to overproduction and globalization. The investment rate has been declining for decades (Zinn 2015, 38). Zinn talks of a „stabilization of accumulation“ (41). With productive investments declining and continuing to decline -the Corona crisis will worsen this trend-, acquisitions of companies by institutional investors interested in the short-term disintegration of a company are on the rise. Confronted with declining profit rates in commodity production, „investment markets act as an elixir of growth“ (43). The economy is becoming financialized. Given that investment opportunities are limited, capital seeks investment areas and lures investors to public institutions. These increase the appetite of investors because of the certainty of demand. Nevertheless, the monopolistic position of, for example, public enterprises, transport companies or energy companies is often very promising. The privatization trend of state-owned companies to date can be explained by this. After taking the form of private law, they are placed under the accounts of companies. Services are offered on a market or public-private company model and become dependent on purchasing power.

By means of financialization and privatization, the surplus value created by society no longer increases even minimally the overall profit of society. Income and wealth inequality has increased, in a way that has not happened for a century (Piketty 2020). We must also add the poverty of citizens – this is the focus of our criticism – especially at the level of municipalities with state service administrations, which makes new privatizations attractive.

But it does not end there. Capital has been able to generate profits by satisfying basic necessities of life such as housing and spatial mobility. We could also argue: Capital is now implementing on a general social level what the capitalist did with the Truck system criticized by Marx (paying workers in kind) and continues to implement today in some places (MEW 23, 493, 696). In the Truck system, the worker had to live in the residences rented by the employer and buy the food sold by the employer, and this continues today, making the worker completely dependent on the employer.2 The employer even takes out of the worker’s pocket the remaining part of the value created by them as wages.

However, we should not make a distinction historically between the following two forms of dispossession: a.) the looting of pre-capitalist society with expropriation of land, water, forests, basically, in the context of natural wealth and including traditional knowledge, and b.) the privatization of public institutions and services in advanced capitalist societies. In the first case, the question is to seize the constituent elements of capitalist evaluation processes, that is, „primitive accumulation“. In the second case, the question is to nullify what is the result of the wars of social distribution of surplus value.

For David Harvey, „the strategy of dispossession remains at the core of the capitalist world“ (2015, 80; see. 2007, 90). This view is in line with that of Rosa Luxemburg, who believed that capitalist accumulation, based on coercion, whether economic or non-economic, requires an uninterrupted dispossession. Harvey uses the concept of „accumulation by dispossession“ as opposed to the historical concept of „primitive accumulation“. This may be done using military force, as in some countries of the Global South. Nowadays, it involves strategies that include corporate directives from the financial market or supranational institutions or the power of the market directly. Harvey sees the structural adjustment programs of the international Monetary Fund as a step to „impose accumulation through dispossession in different areas and societies“ (2007, 92).

Dispossessions are peculiar to the capitalist mode of production. In first place, it requires the rationality of large-scale production, concentration and centralization, which in turn implies the cost of the economic existence for small producers, artisans and peasants if they do not manage to survive as sub-industrial enterprises. In second place, there is the requirement of raw material and energy from mines, dams, etc. Their construction necessarily entails the destruction of the habitats of the communities, often to the point of their expulsion. Externalization of the ecological cost creates the same situation. The dispossession of the whole of society occurs with the public rescue measures prepared for companies that are declared „vital to the system“. For Karl Georg Zinn, the rescue packages mean „the de facto privatization of public finance“ (2015, 64).3 Likewise, this indirect privatization has turned into a new model of capital revaluation: the privatization of infrastructure and public services. For the Hasankeyf Valley settlements, the dispossession is obvious and brutal, but not so general.

Sources:

Foster, John B./ Clark, Brett (2020): The Robbery of Nature: Capitalism and the Ecological Rift. New York.

Harvey, David (2015): Siebzehn Widersprüche und das Ende des Kapitalismus. Berlin.

Piketty, Thomas (2020): Ökonomie der Ungleichheit. Eine Einführung. 3. Aufl. München.

Whitfield, Dexter (2020): Public Alternative to the Privatisation of Life. Nottingham.

Zinn, Karl Georg (2015): Vom Kapitalismus ohne Wachstum zur Marktwirtschaft ohne Kapitalismus. Hamburg.

* This article was first published in the 28th issue of

PoliTeknik: http://politeknik.de/p11936/

- population that reached 10,000 people was displaced.The administration relocated 2,000 of them to other regions.

- A current example is the exposed and scandalized situation of the meat industry during the Corona crisis.

- During the financial crisis of 2008/09, 1.6 billion euros were spent on "system-critical" banks across the EU.cion-2021/file.html