Prof. Sanjoy Roy

Department of Social Work, University of Delhi – INDIA

There is less tranquilly and serenely in the world now than there was a decade ago. A worldwide recession is imminent as economic instability continues to escalate. Post-Cold War democratisation has reached a critical juncture across the world in reverse motion. Devastating effects are being reaped from climate change. While new wars are boiling to the surface, the hostilities in Syria, South Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan, Maynamar are still raging. However, despite the fact that there are more and more issues in the world, those national governments are getting worse at fixing them. In most cases, it would appear that national governments do not have the intestinal fortitude to accept creative and comprehensive solutions. The concept of multilateralism, which calls on states to cooperate, has reached a dead end.

The UN was envisioned by its founders as the centre of global political and economic relations and as a body with the authority and capability to address the most important issues facing humanity. Three major commitments formed the basis of the UN. To uphold international peace, to resolve international issues of a cultural, social, economic, or humanitarian character and to encourage and protect human rights. (Nadin, 2019)

UN’s Success

The UN has successfully promulgated standards on refugees, internal conflict, civil protection, displaced persons, and the duty to protect. When governments are faced with ambiguous situations, prescriptive rules also play a part in guiding their foreign policy. These norms frequently impact how decision-makers formulate their policies, whether or not they really materially alter state action. There is minimal debate over the importance of the UN’s primary humanitarian initiatives, UNICEF, UNHCR, and the World Food Programme. Through OCHA, the UN oversees relief efforts for victims of both natural and man-made catastrophes across the world. The UN is often successful and competent in its capacity. (Nadin, 2019)

UN’s Failures

There are certain grave issues in the World like mistreatment of women by UN peacekeepers, the spread of cholera in Haiti, controversy around oil-for-food, the genocide in Rwanda, the murmurderous rampage at Srebrenica. The list of shortcomings is indicative of a larger group of structural ailments that are important to take into account. Understanding civil wars is challenging because they are sparked and then driven by a number of interrelated variables, such as economic resentment, sectarian conflict, societal institutions, and remnants of colonial control. Local, regional, and international players are frequently perplexed by the complexity of contemporary conflicts, which confuses their reactions. Intergenerational conflicts have emerged in Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Afghanistan, Iraq, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan and many more. Conflict has profoundly changed the basic foundation of these communities. Even if it is seen as a legitimate and neutral entity, the UN’s capacity to succeed in these situations is severely constrained. In spite of the fact that prevention is preferable to treatment, the United Nations is and most likely will continue to be a reactive organisation. This means that it will respond to crises after they have already occurred rather than try to prevent them in the first place. Since the conclusion of the Cold War, every Secretary-General has emphasised the value of prevention, but to no purpose. As was previously said, crises are frequently insoluble due to their complexity and intractability. This just helps to emphasise how crucial prevention is. However, the system will never permit such a philosophical change since it would pose an intolerable threat to national security. (Nadin, 2019)

The UN has likely drifted even farther away from current realities and interests than before, falling well short of this aim. The global power structure has undergone significant transformation. The number of members has more than tripled, several emerging nations have become significant players in world politics, and some sovereign autonomous regions have been created. The end of the cold war also marked a significant shift in the balance of power on the global stage, paving the way for a non-ideological epoch of international diplomacy. The apparent replacement for the ideology-driven politics of the past is the growing significance of economic strength in international affairs. Furthermore confronted with 1.3 trillion dollars‘ worth of foreign debt owed by emerging countries, which is ruining their countries‘ economy. The UN is essentially operating in new territory. The convergence of all these trends and shifting dynamics presents a singular opportunity for a re-evaluation of assumptions and a reorganisation of power relations in the UN. (Rajamani, 1995)

For instance at the present stage, President Zelensky, President of Ukraine recently questioned the UN Security Council’s function, saying that the organization’s attempts to stop the Russian attack on Ukraine were fruitless. In order to address the present dangers to international security, the Security Council urgently needs to be Reformed.

My argument and comprehension is that the transition from unipolarity to multipolarity, structural changes including the emergence of developing and third-world countries, and the increase in global population all reflect the changing structure of the international system in the twenty-first century. All of these factors contributed to the need for the U.N.O to become more democratic by increasing the number of U.N.S.C members. This demand rose to prominence as a result of the U.N.S.C’s existing membership failing to adequately reflect the geo-political environment at the time. The Security Council is the important organ of the United Nations, and the ongoing need to increase membership and transform it into a body that represents the modern world will be crucial in resolving disputes on a global scale. The present composition of the council includes five members who are appointed to serve in a permanent capacity and 10 members who serve in a capacity that is not permanent. The main issue with the UNSC’s current structure is that it exclusively represents Elite class of nations, which makes it unsuitable for the requirements of the world today. Other countries are unhappy by the U.N.O’s inability to make changes and turn it into an underrepresented body. In the end, this leads to an imbalance in the relationships between the permanent members and other member nations in the power structure. Many nations are concerned about the UNSC’s Undemocratic Representation, and the absence of strategically significant nations like Germany, Brazil, Japan, and India raises questions. Together, India and a number of other nations mobilised to demand the Security Council’s refurbishment. Since the conclusion of the cold war, a number of proposals for U.N.S.C reform have been proposed. The G4 countries i.e. India, Brazil, Germany, and Japan are noted for their numerous projects. The G4 nations‘ plan, which advocates increasing the number of Security Council members from fifteen to twenty-five, is intended to help them gain permanent participation in the council. Even while all of the member nations agree that the council should be expanded, little has actually been done since the P5 nations are reluctant to share authority. (Francis, 2022)

Following its attainment of independence 75 years ago, India has emerged as one of the key forces in international affairs. India has assumed the role of leader in the movement to reform the international organisations in order to bring about a New International Economic Order (NIEO). India, a significant global power, has urged for changes including inclusion, representation, and democratisation of international organisations such as the United Nations Security Council, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organisation. In times of crisis, India has been a leader in calling for international solidarity and joint action. India’s permanent membership in the United Nations Security Council is the source of the most powerful voice in support of the change. Through multilateral diplomacy and the formation of organisations such as IBSA (India, Brazil, and South Africa) and G4 Nations (Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan), India is pushing for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi assumed office, India has been relentless in its pursuit of a permanent member with veto power on the United Nations Security Council. A considerable contribution to the United Nations (UN) might be made by India’s dedication to non-violence and disarmament. In addition, India took a stance to support the principle that international bodies should operate in a non-discriminatory and transparent manner. India has often said that it is a responsible nuclear weapons state and that it will not deploy its nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states as a deterrent. The NPT (Non-Proliferation Treaty) has been the target of frequent Indian criticism for its perceived bias and lack of democracy. The United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operation, development objectives, sustainable development, climate change, and anti-terrorism initiatives are some of the international events and treaties in which India has been an active player. More than 200,000 Indian officers are now serving at United Nations peacekeeping deployments. Additionally, India has made contributions to the United Nations in order to combat global issues such as terrorism, climate change, energy security, the refugee crisis, pandemics, and the reformation of the present international economic world order. (Lalitha & Kumar, 2022)

Nevertheless, the United Nations Charter does not specify the requirements needed to become a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. Indian foreign policy has evolved from non-alignment to multi-alignment, demonstrating the country’s confidence in its ability to work effectively with both large and minor players in the international system. The expansion of India’s economy, size, democratisation, political stability, increase of soft power, nuclear power, and military strength, as well as its position as a growing power in the South Asian area, are all factors that may be used to argue for India’s participation in the organisation. (Lalitha & Kumar, 2022)

When the world is looking for a replacement for the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), which has been immobilised by the veto, India has arrived at the ideal time thanks to the alphabetical rotation of the G-20 chair. The UNSC’s reputation was at its lowest point most recently during the COVID-19 epidemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The permanent members, together with a sizable portion of the General Assembly, will fight tooth and nail against any effort to restructure the United Nations Security Council, especially if it involves increasing the number of permanent members. India’s first move should be to draw attention to the Bali Declaration, submit a road plan during the G-20 preparations, and encourage the sherpas to include it on the agenda. Only Russia may respond negatively since it must bargain on an equal footing with the other G-20 members. Even Russia will accept India’s position as an honest broker in the process if Russia is searching for a way out. This will improve India’s ability to address the problem in a G-20-approved manner. It will achieve India’s ultimate objective of obtaining UNSC reform. The UNSC can formalise the decision and put it into effect for global peace and security once the preliminary work is finished. (Sreenivasan, N.D.)

Although there isn’t a consensus on how the Council should be altered, the majority of proposals call for expanding the fifteen-member body, typically by adding new permanent or semi-permanent members. Inability to settle on a single plan for Security Council reform led the Secretary-General’s High-level Panel to provide two different suggestions. The Council now has a total membership of 24 in both forms. While Model B provides a new category of eight four-year renewable seats, Model A adds six new permanent seats. In order to make the Council more „Democratic“ and „Accountable,“ the Panel came to the conclusion that a decision about its expansion is „now a necessity.“ (Nicol, 2006)

If the council is enlarged will it be successful?

Supporters of the reform argue that the Security Council needs revamping since its existing structure is ineffective. However, it is unclear whether this inefficiency is brought on by the Council’s size or by the diversity in the security policy preferences of its decision-makers, which results in less coordinated action for the advancement of global security. What assurance is there that a larger Council (20-23 members according to most reform suggestions) will be more effective and unified in its decisions about various global issues? It is therefore questionable whether an expanded Council will better achieve the goal of preserving international peace and security.

Veto Right- In particular, the G-4 and the African Bloc, which compete for membership on the Security Council, insist on the ability to veto. According to the African Bloc, it is crucial that new permanent members of the Council be granted the veto power for the sake of democracy and equality in the World. If the Council of the „P5“ cannot come to an agreement on many global issues, how could an expanded council of about 11 permanent members be effective and unified? In fact, the new permanent members may acquire a tendency to use their veto authority only to make their presence known, putting this expanded Council at a high danger of deadlock. It is crucial to know that the Council will not become more effective or competent by adding more veto players to the decision-making process. However, ensuring the independence of Council decision-making and the openness of Council processes, with broad acceptance, is what will increase the Council’s effectiveness and efficiency. It is important that all members of the Council have the ability to operate freely and make decisions without facing any kind of interference or pressure from the other members of the Council, whether they are permanent or not.

Taking into account fair regional representation; Council’s size- The aspirant member states‘ demand that the Council take into account the organization’s diverse regional makeup being wholly legitimate. However, it is unclear how any nation may serve as the Security Council’s de facto representation of its region. The only way for regional representation to be effective is if all countries within a region agree on a single country to represent them as a permanent member of the Council and that country pledges to prioritise the interests of the region over its own. A difficult job for any aspirant state will be prioritising regional interests over national ones. (Sarwar, 2011)

Weighted Voting in the General Assembly– The general assembly, where each nation, regardless of size, has one vote, is an area free of conflict. This is unquestionably democratic, but it frequently suffers from the dictatorship of numbers. JF Dulles proposed a two-tier voting system in which each state would have an „Assembly vote“ that reflects the sovereign equality of all states and grants each state an equal vote, as well as a system of „weighted voting“ that would allow the outcome to roughly indicate a verdict in terms of also ability to play a part in world affairs. Weighted voting may initially appear undemocratic, but it is important to keep in mind that if the assembly is to take on greater responsibilities, there must be a mechanism in place to prevent countries from imposing their own serious military or financial obligations on other countries.

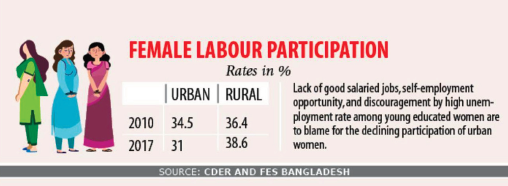

Gender Justice in the UN– According to Article 8, the UN shall not impose any limitations on the admissibility of men and women for involvement in its major and subsidiary institutions in any capacity and on an equal basis. Despite being referred to as „obvious“ and „redundant,“ this clause was introduced at the San Francisco convention (1945) on the insistent demands of women’s organisations. Unfortunately, even the modest promise of Article 8 has not been kept today, despite the charter having been in effect for close to 50 years. Although there have been general assembly resolutions aimed at increasing the percentage of women in the UN system from the current 20% to 25% by 1995. Not much has been accomplished. The most professional positions are still solely reserved for men. There aren’t many women officials in organisations like UNICEF. Only 4% of the senior executive workforce at the UN were women up until 1990. This is a dismal track record for a group that only advocates for equality on the surface. Today, the UN has been accused of engaging in gender racism. The implications are staggering. Gender equality policies won’t be implemented if women aren’t empowered even at this level, and the equality of the sexes will only ever exist in theory. (Rajamani, 1995)

Conclusion

Since the Special Committee in 1975, recommendations for UN reform have been given about 20 years of consideration. The majority of the recommendations stated in this paper for a more powerful and democratic UN have likely been made before. Political will to make the necessary reforms didn’t exist back then, and it presumably won’t exist now either. The council’s permanent members will be willing to give up their privileges for the „greater good of mankind,“ but the play of vested interests will invariably cause the organisation to collapse. I believe that any multinational organisation must function within these constraints. At the tenth UNGA session, Indian delegation head Krishna Menon stated, „Unless you have unanimity we cannot amend the charter and if there is unanimity, the justifications for revising it will be very modest.“ Perhaps it is impossible to change the charter in the current political climate such that it more accurately reflects global aspirations. However, that has no bearing on the UN’s continued existence. In its 78 years of existence, the UN has made significant advancements in the creation of a global community and has unquestionably justified its existence in other ways as well. Here, an analogy from under-secretary general for special political affairs Brian Urquhart appears suitable. „This city has a high crime rate, but it does not justify calling for the dissolution of the police department. On the contrary, it creates a need for its enhancement. Therefore, democratisation of UN is very much required now when we see the World politics and dominance of few, so that equality and equal responsibility can be sustained in the world.

* This article was first published in the 37th issue of PoliTeknik. The text appeared in Turkish in the printed magazine and in English in the online publication:

– Turkish text: PoliTeknik Nr. 37, page 12, 13.

– English text: https://politeknik.de/p13531/

References

• Lavanya Rajamani. (1995). Democratisation of the United Nations. Economic and Political Weekly, 30(49), 3140–3143. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4403537

• Nadin, P. (2019). The United Nations: A history of success and failure. AQ: Australian Quarterly, 90(4), 11–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26773344

• Sarwar, N. (2011). Expansion of the United Nations Security Council. Strategic Studies, 31(3), 257–279. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48527660

• Lalitha, S & Dr. Kumar, K.A. (2022). Why India should become a Permanent Member of UNSC?. The Kootneeti. Retrieved from https://thekootneeti.in/2022/01/17/why-india-should-become-a-permanent-member-of-unsc/

• Francis, T. (2022). Democratization of United Nations. The Kootneeti. Retrieved from https://thekootneeti.in/2022/05/18/democratization-of-united-nations/