Santo Di Nuovo

picture: Created with AI

The sustainability paradigm

The term “sustainability” was coined firstly at the 1972 United Nations Human Environment Conference in Stockholm. In 2015 was published the U.N. Agenda for Sustainable Development1 that included several goals. Among these, one regards empowering vulnerable people: “Those whose needs are reflected in the Agenda include all children, youth, persons with disabilities (of whom more than 80% live in poverty), people living with HIV/AIDS, older persons, indigenous peoples, refugees and internally displaced persons and migrants. We resolve to take further effective measures and actions, in conformity with international law, to remove obstacles and constraints, strengthen support and meet the special needs of people living in areas affected by complex humanitarian emergencies and in areas affected by terrorism” (n. 23).

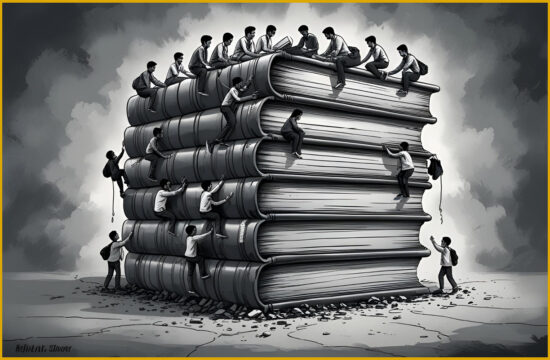

The aim is to provide inclusive and equitable quality education at all levels: Early childhood, primary, secondary, tertiary, technical and vocational training. All people “should have access to life-long learning opportunities that help them acquire the knowledge and skills needed to exploit opportunities and to participate fully in society” (n. 25).

Sustainable development involves designing and implementing programs, processes, and actions that balance economic development, environmental protection, social well-being, to meet the needs of both present and future generations. Thus, sustainability denotes a social goal to be implemented by social policies, consolidating the field’s traditional focus on education, career development and vocational behavior at the individual and social level (Ogryzek, 2023). Broadening career development to larger social systems, it can further promote human health and well-being, equality, quality education, decent work for all people (Di Fabio & Cooper, 2023; Nota et al., 2020).

What role for Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

Essential principles for AI systems useful for sustainability are:

– Prevention from risk: AI should be designed and used in a way that prevents any risk or harm.

– Respect for human autonomy: individuals should have control over how AI interacts with them and the data AI collects about them. AI should be transparent and able to provide understandable explanations for its decisions

– Equity: AI should be designed and used fairly. This means that AI should not discriminate against or favor certain groups of people. In addition, AI benefits should be distributed equitably in society.

The AI-Act of the European Parliament, June 2023)2 is the first legal framework for the management of artificial intelligence in the European Union. Main principles of this Act are:

1. Transparency: AI systems must be clear and understandable to users. Users should be able to understand how an AI system makes its decisions.

2. Accountability: the design of AI systems should ensure accountability and traceability, that is, the ability to track the decision-making process of an AI system.

3. Non-discrimination: AI systems must not be discriminatory on the basis of gender, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, sexual orientation or other criteria.

4. Safety: the design and implementation of AI systems must ensure the safety of people from risks caused by them.

5. Data integrity and privacy: AI systems must respect the integrity and confidentiality of personal data, without invading people’s privacy, or using personal data without consensus.

6. Respect for the environment. No additional weight should be charged on the world ecological system, supporting all the actions aimed at ensure physical and environmental sustainability.

The rules can be reassumed in the “3H“ criteria: Helpful, Honest, Harmless. AI should support human intelligence and activity, but respecting its autonomy without risks.

How to cope with AI risks

Nick Bostrom already in 2014 underlined the risks of a “superintelligence” overwhelming the human intelligence. Many “godfathers” of AI, including Faggin and the Nobel Prize Hinton, warned from the risks implied by AI’s rapid evolution3. Lindgren (2023) reported the critical studies on AI in different applicative fields. The risks regard all the technologies based on AI, as virtual and augmented reality, chatbots, and robots.

An example of specific risks regards Generative AI (GAI), i.e., a system that uses existing information to create new content. Large Language Models (LLMs) are neural networks trained on vast amounts of text data to understand and generate human-like text, and used for production of texts and images, question answering, and translation. LLM-based agents (e.g. ChatGpt, Gemini Deep Mind, Character.AI, and similar) are widely diffuse especially for learning and formation, but also in working contexts (Sabesan et al., 2025).

These instruments could have risks mainly at the semantic level, inferring from human language inaccurate, biased, misleading, or sometimes “toxic”, modalities (Weidinger et al. 2022; Shelby et al. 2023; Pan et al. 2023). “Risks include large-scale social harms, malicious uses, and an irreversible loss of human control over autonomous AI systems. Although researchers have warned of extreme risks from AI, there is a lack of consensus about how exactly such risk arise, and how to manage them” (Bengio, et al. 2024, p. 842). So far, scientific literature has given little consideration to the harms of LLMs, of the tensions that arise in the pragmatics of spontaneous and situated social interaction (Kasirzadeh and Gabriel 2023).

We will consider a specific aspect of the possible risk, related to creative production.

Can generative AI enhance or reduce creativity?

Creativity in humans is not limited to generate ideas or images, or to rearrange in a different way previous materials. It requires the desire of an individual to create something original (intentionality), and the capacity of estimating the potential originality and effectiveness of the generated content (evaluation).

“Both problem finding and estimation of creativity require self-regulation and social co-regulation through which initial ideas and drafts of potential outputs are developed and refined. Self-regulation and co-regulation add new ideas to the initial ones, revise based on reflection and feedback, and opt for more or less unconventional approaches, all of which is unique to humans, and all of which contributes to overall creativity … The aforementioned results produced by GAI are only valuable and “exciting” because we, humans, attribute that value and feel that emotion. Present-day GAI is unaware of both value and related emotions” (Vinchon et al., 2023, p. 4).

AI can be an effective aid during some parts of the creative process; but humans are at risk of being totally eliminated from the process, avoiding higher-level decisions about questions to ask, parts of the text or images to keep, final production to choose.

The impact of AI-generated images on creativity, particularly in divergent thinking ability, has been studied empirically, to study how exposure to visual content produced by generative AI systems influences the production of creative ideas during visual ideation tasks. The use of AI was associated with less rich creative output, characterized by a lower number of ideas and lower variety and originality. While generative AI provides structured support to the generation of ideas, it can also introduce cognitive constraints that inhibit the free and divergent exploration of creative thinking. (Wadinambiarachchi et al. 2024).

Adolescents tend to view generative AI as a useful tool for tackling complex schoolwork, perceiving it as a facilitating and accessible support. This is an advantage for accessing resources and immediate support, but excessive or unmediated use of these technologies could lead to cognitive dependence, increasing difficulty in performing autonomous processing and developing problem-solving strategies.

Educational guidance is needed to avoid passive use and develop greater decision-making autonomy in interacting with AI (Klarin et al., 2024).

The need of “collaborative” intelligence

Systems based on LLM and generative IA should be designed to foster variety and flexibility in ideas, avoiding the risk of encouraging the repetition of pre-established patterns and dependence on initial machine input. We need an artificial intelligence that doesn’t constrain natural intelligence into pre-established patterns, but stimulates its capabilities and extending its possibilities.

Can AI share with humans the methods of “collaborative intelligence” used in real life?

Collaborative intelligence is the capacity of actively cooperating to improve the common performance, sharing aims and outcomes, entertaining interactions useful for the task. Synchronic communication is requested.

Applications based on A.I. can support, implement, and enhance human intelligence, but real collaborative intelligence requires continuously shared cognitive activities and contents. Therefore, it need to develop reciprocal (not only instrumental) and synchronic (not only sequential) communication (Di Nuovo, 2023).

Human creativity can be enhanced by collaborative AI, modeled on collaborative human intelligence, an effort involving more or less equally the human and the generative AI, with recognition of the contributions of each party. This can be called “Co-cre-AI-tion”: creativity is augmented because the output is the result of a hybridization not possible by humans or AI alone. “We are in a new era of ‘assisted creativity’, namely AI is not an independent creator in this sense, but rather a collaborative creative agent” (Winchon et al., 2023, p. 4).

AI will support all the jobs that can be automated. The contents generated by AI are based on mixtures of existing content previously generated by humans and then fed to the AI system during a training phase. This ‘mash-up’ can be rearranged originally, but it is not really creative. The responsibility for the real novelty of the final product must be left to the human intelligence.

Educative and formative processes should avoid ‘Plagiarism 3.0’, i.e., the desire to appear productive and creative “drawing” heavily on AI productions without citing the source. At the same time, ‘Shut-down’ of human creativity should be avoided. People might become less motivated to conduct creative action, feeling of not being able to create at the same level as AI and, thus, outsource the creation of content to generative AI. “Generative AI tools like ChatGPT are reshaping the educational landscape”, conclude Küchemann et al. (2025).

A useful example of an educational tool demonstrates how effective human-AI interaction strategies can significantly impact user engagement and decision-making.

Yamamoto (2024) proposed a novel chatbot strategy, employing suggestive endings inspired by the ‘cliffhanger’ narrative technique (i.e., suspense about conclusions). By ending responses with hints rather than conclusions, the chatbot stimulates users’ curiosity and encourages deeper engagement. An online study demonstrates that users interacting with the suggestive chatbot ask more questions and engage in more prolonged decision-making processes, highlighting the potential of strategic AI communication to foster critical thinking.

Conclusive remarks

Mollick (2024) speaks of “Co-Intelligence”, urging to engage with AI as co-worker and co-teacher.

To be truly collaborative, AI applications should

– support human motivations, including emotional domains, without limiting to mere pre-programmed instrumentality;

– actively cooperate, improving joint performance, sharing goals and outcomes, and entertaining task-useful interactions:

– enhance complementarity and dynamic interaction, beyond a simple division of work or a static transactional relationship.

We should move toward collaborative, not just supportive, nor substitutive AI.

Collaborative AI in art, industry, health care, emergency services, and educational work, improves both efficiency and creativity in solving human problems. It counteracts prejudicial motivations, e.g., fear of being overwhelmed, or the opposite tendency to delegate to the technology essential parts of human work.

This cooperation realizes true conjoint natural-and-artificial intelligence. AI should reflect complex human social and psychological processes: synchronic communication, autonomous motivation, adaptive emotions.

AI can be useful for sustainability if it is planned (and used) to become truly collaborative, acceptable, and not dangerous to humanity and to its development.

An essential aspect to make AI really collaborative with human cultures regards sharing values. They cannot be derived by a globalised culture, typical of social media from which GAI derives its content. Values should be autonomously chosen by individuals and social groups in each specific culture, and education should foster the choice of pro-social values rejecting the anti-social ones. Also in this sense GAI challenges the educational landscape.

Ultimately, the cultural and political domain is involved and challenged: The impact of AI involves not only cognitive aspects of individuals, but the broader society.

Lindgren’s (2023) handbook provides in-depth reviews of social, ethical and political implications of AI, including the risk of bias and discrimination, its impact on democracy and governance, and the use of AI technologies in decision-making processes, in different fields of social life.

As stated in the previously cited U.N. agenda for sustainable development, all people, without restrictions for personal and social variables, should have equitable access to life-long learning opportunities that help them participate fully in society. IA must support these goals, overcoming (and not increasing) differences and restrictions within Nations and between them.

For this aim, each Nation—going beyond recognizing the usefulness of current AI technologies—should regulate the use of AI technologies based on its own specific conditions and pro-social values, particularly in education and work systems.

Moreover, considered the global nature of most AI services and systems, a supranational regulation is also needed, and U.N. should engage for this.

A debate should be promoted about what way the aims of sustainability can be pursued – both in national and international contexts – to promote efficient, creative, safe, healthy work and social life for all people of our world.

References

Askell, A., Bai, Y., Chen, A. et al. (2021). A general language assistant as a laboratory for alignment. arXiv:2112.00861. Doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2112.00861

Bansal, P. (2019). Sustainable development in an age of disruption. Academy of Management Discoveries, 5, 8–12. https:// doi.org/10.5465/amd.2019.0001

Bengio, Y., Hinton, G., Yao, A. et al. (2024). Managing extreme AI risks amid rapid progress. Science, 384(6698), 842-845.

Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press.

Di Fabio, A., Cooper, C. L. (Eds.). (2023). Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development in organizations. Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Di Nuovo, S. (2023). Could (and should) we build “collaborative intelligence” with Artificial Agents? A social psychological perspective. QEIOS, LHEU38. https://doi.org/10.32388/LHEU38

Faggin, F. (2022). Artificial Intelligence Versus Natural Intelligence. Springer.

Faggin, F. (2024). Irreducible. Consciousness, life, computers, and human nature. Essentia Books.

Kasirzadeh, A., Gabriel, I. (2023). In conversation with artificial intelligence: Aligning language models with human values. Philosophy and Technology, 36(2):27. Doi: 10.1007/s13347-023-00606-x

Kenton, Z., Everitt, T., Weidinger, L., Gabriel, I., Mikulik, V., Irving. G. (2021). Alignment of language agents. arXiv: 2103.14659. Doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2103.14659

Klarin, J., Hoff, E. V., Larsson, A. (2024). Adolescents‘ use and perceived usefulness of generative AI for schoolwork: Exploring their relationships with executive functioning and academic achievement. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 28(7):1415782. doi: 10.3389/frai.2024.1415782

Küchemann, S., Rau M, Neumann K., Kuhn J (2025) Editorial: ChatGPT and other generative AI tools. Frontiers Psychology, 16:1535128 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1535128

Lindgren, S. (Ed.) (2023) Handbook of Critical Studies of Artificial Intelligence. Elgar.

Mollick, E. (2024). Co-Intelligence: The definitive, bestselling guide to living and working with AI. Allen.

Nota, L., Soresi, S., Di Maggio, I., Santilli, S., & Ginevra, M. C. (2020). Sustainable development, career counselling, and career education. Springer.

Ogryzek, M. (2023). The sustainable development paradigm. Geomatic and Environmental Engineering, 17, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.7494/geom.2023.17.1.5

Pan, L., Saxon, M., Xu, W., Nathani, D., Wang, X., Wang, W.Y. (2023). Automatically correcting Large Language Models: Surveying the landscape of diverse self-correction strategies. arXiv:2308.03188. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2308.03188

Sabesan, K., Sivagamisundari, Dutta, N. (2025). Generative AI for Everyone: Deep learning, NLP, and LLMs for creative and practical applications. BPB Publications, India.

Schleiger, E., Mason, C., Naughtin, C., Reeson, A., Paris, C. (2024). Collaborative Intelligence: A scoping review of current applications. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 38(1), n. 2327890. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2024.2327890

Shelby, R., Rismani, S., Henne, K. et al. (2023). Sociotechnical harms of algorithmic systems: scoping a taxonomy for harm reduction. arXiv:2210.05791. Doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2210.05791

Sison, A. J. G., Daza, M. T., Gozalo-Brizuela, R., Merchán, G., César, E. (2023). ChatGPT: More Than a „Weapon of Mass Deception“ Ethical Challenges and Responses from the Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HCAI) Perspective. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40(17), 4853–4872. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4423874

Winchon. F., Lubart, T., Bartolotta, S., et al. (2023). Artificial Intelligence & Creativity: A Manifesto for Collaboration. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 0, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.597

Wadinambiarachchi, S., Kelly, R. M., Pareek, S., Zhou, Q., Velloso, E. (2024). The effects of Generative AI on design fixation and divergent thinking. Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–18). Association for Computing Machinery.

Wang, Y., Zhong, W., Li, L., et al. (2023). Aligning Large Language Models with Human: A Survey. arXiv:2307.12966. Doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.12966

Yamamoto, Y. (2024) Suggestive answers strategy in human-chatbot interaction: a route to engaged critical decision making. Frontiers in Psychology 15:1382234. 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1382234

1 https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

2 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206

3 https://safe.ai/work/statement-on-ai-risk