Hüseyin Ozan Uyumlu

TEACHER • TÜRKİYE

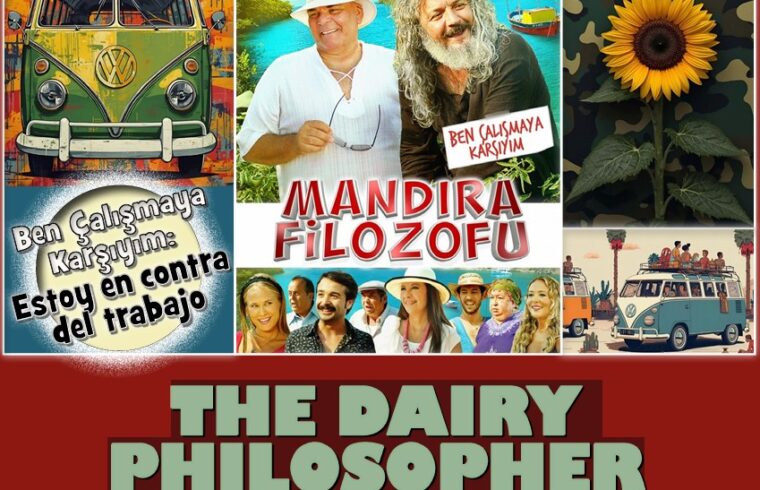

The movie “Mandıra Filozofu” (The Dairy Philosopher), directed by Müfit Can Saçıntı, was released in 2014. The comedy movie, with screenplay written by Birol Güven, reached a wide audience in Türkiye. The film featured a star cast, including Müfit Can Saçıntı (Mustafa Ali), who also directed the movie, Rasim Öztekin (Cemil), Ayda Aksel, Kemal Kuruçay, and Defne Yalnız.

The protagonist of the movie, Mustafa Ali, has a degree in Philosophy. Mustafa Ali, who is completely opposed to work, lives by the sea, in contact with nature, far from everything that modern life entails, and spends almost all his time reading books. Cavit, another important character in the film, is a smart and hard-working businessman who arrives in the village of Çökertme, located on the Gulf of Gökova in the Milas district of Muğla province, to carry out his new project. His aim is to purchase the land belonging to Mustafa Ali and build a boutique hotel on it to make a profit. Mustafa Ali opposes the urban lifestyle, consumer habits, and ambition that Cemil represents. The film deals with the contrasts between city and village, modernity and nature, production and consumption, freedom and dependence through the conflict between these two characters.

At first glance, the film appears to be an apology for a “return to nature” and a “simple life” as opposed to the fast-paced, stressful, and alienating urban life imposed by the capitalist system (without mentioning capitalism by name). The character of Mustafa Ali is portrayed as a popular philosopher who demonstrates that it is possible to live a quiet life, far from money. The movie argues that being in touch with nature, not consuming, and living a simple life is morally correct. We can play devil’s advocate and criticize the film which conveys the message that “one can be happy without having anything”. Simon Kuper has a book

titled “Football Is Never Just Football”. Let’s apply this brief, effective, sloganized phrase to the film industry as well: “Cinema is not just cinema.” From this starting point, we can offer a critique focused on “property” without neglecting the humanitarian messages of the Dairy Philosopher.

Mustafa Ali, despite appearing to be a “wise man living on the margins of society,” is in fact a figure who owns land, animals, and a house. In other words, he is not completely detached from the material conditions of the system, but his ability to lead a simple life is based precisely on the security that property provides him. At this point, the film is no longer a production that praises the simple and quiet life, but becomes an “anti-capitalist illusion” that rises with the invisible comfort of property.

Mustafa Ali says throughout the movie that he does not need money or property. However, the place where he lives and his lifestyle demonstrate precisely the existence of the security that property provides. In other words, the land he owns is the guarantee of his “independence”. The animals and the house he owns form the basis of his independent life. At this point, the criticism of the system by the “Dairy Philosopher” is only possible thanks to the comfort provided by property. Therefore, the character is not actually a proletarian or precarious subject, but a small farm owner. This means that Mustafa Ali’s criticism of the system remains within the realm of “romantic anti-capitalism.”

Mustafa Ali represents the modern individual’s desire to return to nature, and when he advises the character of Cemil (Rasim Özetekin), a very wealthy man, to “flee the city,” he is actually advising the audience as well. However, it is important to note that these messages, which seem easy to convey, are not as easy to put into practice. Has Mustafa Ali really “dropped out of the system,” or is he criticizing the system from a position of security afforded by his property? So is Mustafa Ali in a good financial situation?

We have all dreamed of “leaving everything behind and moving to a village” at some point. Escaping traffic, meetings, and endless notifications to find peace while milking cows at the dairy farm… The Dairy Philosopher was precisely the cinematic representation of that feeling. It contrasted nature with the artificial life of the city, and peace with money. For many viewers, that was “true wisdom”: To be satisfied with little, not to consume, to remain outside the system. But this is precisely where we must ask ourselves: Was that philosopher really outside the system? The protagonist of the film, Mustafa Ali, says he lives without the need for money. However, everything he owns—his house, his land, his animals—is the guarantee of that “situation of non-need.” In other words, he is, above all, a property owner. In this case, his “freedom” is equivalent to the luxury of being able to speak from the circle of security provided by his property. Indeed, those who have no land, no house, no cow, not even a chicken, have no opportunity to return to nature. In other words, the Dairy Philosopher does not stand outside the system, but rather on its periphery. He does not open a breach in the system, but merely observes the outside from there. His criticism is not structural, but romantic. He does not target money, property, or production relations, but rather the “state of mind of the urban individual.” Like self-help books, he ignores the “infrastructure” mentioned by Marx. In this way, he invisibilizes class differences and creates the illusion that everything can be solved through individual consciousness. In today’s Türkiye, for the millions of people trying to survive on minimum wage, who cannot afford rent and who do not even have the opportunity to enjoy nature, the “simple life” is not an option, but a luxury.

From the moment the movie was released until today, property relations have become much more acute. The situation has turned into a crisis as the issue of the right to housing affects a greater number of people. Capitalist pressure on land, water, and nature has increased. The gap in income distribution has widened. The middle class has been eliminated. In this context, the individual simplicity proposed by “The Dairy Philosopher” has become an almost impossible luxury. Therefore, from today’s perspective, the film can be interpreted as a work that does not oppose the system, but rather appeals to the peace of those who live on the margins of it.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted class differences in the world. Housing and land prices have skyrocketed. The earthquakes in Kahramanmaraş and Hatay (2023) have further exacerbated the crisis. Hundreds of thousands of people have been left homeless, and millions have been forced to take on a heavy burden to meet their housing needs. In November 2025, according to official figures, the inflation rate was 37.15%. According to the latest data from November 2025, the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK) announced an annual inflation rate of 31.07%. According to the Inflation Research Group (ENAG), annual inflation was 56.82%. In light of these worrying figures, current land prices in the location where the movie was shot show that even owning a small property is now a pipe dream for the working class. The situation is serious not only in coastal areas, but also in rural areas of poor cities. Let’s say you don’t need a house, just a tiny house. Their prices are not insignificant ether. The cheapest second-hand tiny house, measuring 32 square meters, costs around 380,000 Turkish Liras. There are also second-hand tiny-houses that are sold for between 2 and 3 million Turkish Liras.

According to data from 2024, the number of salaried workers in Türkiye was 15 million 73 thousand 564 people, and approximately 11.2 million people worked for the minimum wage. In 2025, the net minimum wage was 22,104 Turkish Liras. If we look at the interest rates on loans in December 2025, we see that they start at 3.5% and go up to 5.5-6%. In addition, loans are not granted for amounts greater than a insignificant amount and long terms are not offered. In short, members of the working class cannot save or buy a house, a car, land, a summer home, etc. For them, being able to meet their basic needs, such as housing and food, in the vicious circle of going from home to work and from work to home, would be a “good result.” In other words, apart from earning a living -which is not easy either- workers cannot aspire to anything else.

At first glance, the film offers viewers an alternative to urban capitalist life: A simple life, far from ambition and greed, in harmony with nature, free from consumerist madness, peaceful… While the city dweller is presented as a “deceived,” “corrupt,” and “money-worshipping” figure, the village character is a person who “knows what is right,” is “peaceful,” and “virtuous.” At first glance, this contrast seems to be an opposition between “city and village” and does not constitute an ideological perspective that highlights class differences. The city’s workers with no property or the lower classes who have no opportuni ty to leave the system do not appear in the film. The proposal of a “simple life” remains a privilege accessible only to those who have a certain economic security, while the critique of the city does not reach class boundaries.

The urban character in the film, as someone who “chooses money,” always loses out. However, in today’s world, not choosing money is no longer a question of character, but of possibilities. The Dairy Philosopher omits this structural reality and prioritizes individual virtue over systemic inequality. Thus, the story becomes a tale that appeases the conscience of capitalism: “Look, if you want, you too can live simply,” it says, but it does not question the conditions of ownership necessary for that simple life. The wise words of the village philosopher have a brief therapeutic effect on the urban viewer, but they change nothing. When the film ends, we return to the city; to rent, bills, VAT, excise duty, work, in other words, to our boring lives…

Since ancient times, the answer to the questions “should a comedy film be ideological?” and “can the cruelty of life be shown in a funny way?” has been “yes.” From storytellers to ancient Greek theater, examples have multiplied. In recent times, Charlie Chaplin wrote the book on this subject in the 20th century. In many comedy-drama films starring Kemal Sunal, the poverty, lack of property, and job insecurity of the urban middle class and working class were conveyed to the viewer. Films shot in the 1970s, such as Kiracı, Garip, Yoksul, and Ortadirek Şaban, managed to make the audience laugh and think. In particular, the short phrase “where is my little olive” that appears in the film Orta Direk Şaban had as much impact as a long and grandiloquent tirade, which in theater is often defined as the main actor’s speech, and remained etched in memory as a tragicomic scene. In my opinion, one of the best movies in this context is Mondays in the Sun, which presents viewers with the most comical and sad situations of class in equality. In addition, the comedy-drama film, whose original title is “El buen patrón” and which was released in Türkiye under the name “İyi Patron”, was a notable production due to its success in conveying the problems of the working class and the contradiction between labor and capital. Fernando León de Aranoa wrote the screenplay and directed both films.

In literature, there are concepts such as the human reader and the fellow reader. In other words, the types of readers can change depending on how they approach the work or how they identify with it. Some works also try to create and find their own group of readers. They themselves decide how much distance to keep from the reader. Bertolt Brecht did this in theater, for example; he didn’t want the audience to get carried away by the play. He said, “You have to keep a certain distance and know that this is a play.” He wanted the viewer to be the real subject. For the movie viewer, it is calculated to what extent the script, the dialogue, the sound, and, above all, the camera techniques will immerse the viewer in the movie and allow them to get carried away by it. In movies like Mondays in the Sun, you become part of the events, part of the working class, part of the precariousness. This movie shows real conflicts and, at the same time, dramatizes them. The stronger the link between art and life and reality, the greater its effect. Ofcourse, it cannot be said that The Dairy Philosopher is completely disconnected from reality. But reality is poorly constructed in it. The conflict between the city and the countryside is as fictional and eclectic as the conflict between the center and the periphery in politics. The real problem of the working class is not that they cannot settle in the countryside, but that they cannot survive. If we were to make a list of the rights that the working class cannot achieve, starting with the right to life, which is the most basic of human rights, the list would extend from here to China. Land has become an investment tool that passes from hand to hand, and housing is no longer a right but has become an “object of speculation.” With the increase in income inequality, owning a home and living close to nature is no longer a dream but has become a class boundary. In this context, The Dairy Philosopher takes on an ironic meaning when viewed today: The simple life is now a “neo-luxury” available only to a certain social class.

After 1980, both in Türkiye and the rest of the world, the aspirations to achieve average well-being in society were replaced by the personal ambition to “turn the corner.” “Turning the corner,” which once meant rising from the middle class to the upper class, now presents itself to us in a different version. Those who wish to escape the alienating, oppressive, and exploitative system of the city to build a new life aspire to acquire a farm in the west or south of the country and settle there. In other words, “returning to the village” has become the new way of “turning the corner.” When The Dairy Philosopher was released in 2014, ro

mantic winds blew. But the wind that blew did not favor the worker, but rather the bourgeois class. Since then, a large number of artists, musicians, entrepreneurs, writers, etc., have bought large farms in places such as Bodrum, Fethiye, Seferihisar, Çeşme, Datça, and Lüleburgaz to produce organic food and achieve peace. But it turns out that the working class does not have the power to acquire land even in Yozgat, let alone the places I have mentioned. To find out if it has the power it needs, one would have to ask the union “leaders” of the time, who settled in the coastal areas. My master’s thesis, which I completed in 2009, was about the organization of academics. I made an extra copy of my 220-page thesis and gave it to the leaders of the academic union of which I am a member. In 16 years, I have not received any response. Therefore, I do not believe they have the answer to my question.

The Dairy Philosopher has been acclaimed for its appeal to individual conscience and simple living. However, from a critical perspective, the film invisibilizes the existence of property. It reduces class inequalities to personal preferences. It seeks social solutions in individual escape. Therefore, the movie is not anti-capitalist, but rather a story that “appeases the conscience of capitalism.” A true critique of the system is not found in The Dairy Philosopher, but in the stories of people without property, without security, and deprived of the right to connect with nature. As long as we do not listen to the story of the deprived, the “simple life” will remain an object of consumption, a privilege.