In this paper, I analyze patterns of school achievement among students of immigrant background and suggest evidence-based directions for increasing students’ educational success. Although each social context is unique, some generalizations regarding patterns of achievement and causes of underachievement can be made based on the research evidence. Identification of causal factors, in turn, enables us to highlight instructional interventions that respond to these causal factors.

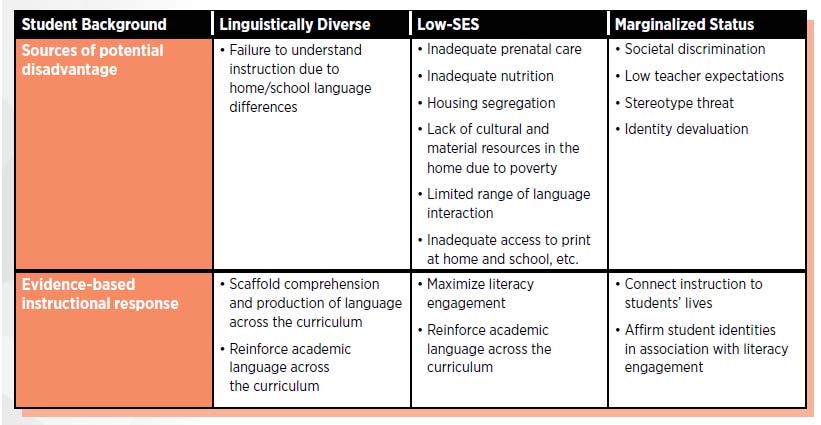

Three potential sources of educational disadvantage characterize the social situation of many immigrant-background communities: (a) home-school language switch requiring students to learn academic content through a second language; (b) low socioeconomic status (SES) associated with low family income and/or low levels of parental education; (c) marginalized group status deriving from social discrimination and/or racism in the wider society. Some communities in different countries are characterized by all three risk factors (e.g., many Spanish-speaking students in the United States, many Turkish-speaking students in different European countries). In other cases, only one risk factor may be operating (e.g., middle-class African-American students in the United States, middle-class French-speaking students attending school in the United Kingdom). Although these three social conditions constitute risk factors for students’ academic success, they become realized as educational disadvantage only when the school fails to respond appropriately or reinforces the negative impact of the broader social factors. For example, the social discrimination that Roma students experience throughout Europe has been educationally reinforced in some countries by educators who label them as intellectually handicapped and place them in segregated special education classes.

School Achievement among Immigrant-Background Students

The reading performance of 15-year-old first- and second-generation immigrant-background students from several countries on the OECD’s Programme for International Student Achievement (PISA) project is shown in Table 1. Students tend to perform better in countries such as Canada and Australia that have encouraged immigration during the past 40 years and that have a coherent infrastructure designed to integrate immigrants into the society (e.g. free adult language classes, language support services for students in schools, rapid qualification for full citizenship, etc.). Additionally, both Canada and Australia have explicitly endorsed multicultural philosophies at the national level aimed at promoting respect across communities and expediting the integration of newcomers into the broader society. In Canada (2003 assessment) and Australia (2006 assessment), second-generation students (born in the host country) performed slightly better academically than native speakers of the school language. Some of the positive results for Australia and Canada can be attributed to selective immigration that favours immigrants with strong educational qualifications. In both countries, the educational attainments of adult immigrants are as high, on average, as those of the general population.

| PISA 2003 Gen 1 | PISA 2003 Gen 2 | PISA 2006 Gen 1 | PISA 2006 Gen 2 | |

| Australia | -12 | -4 | 1 | 7 |

| Austria | -77 | -73 | -48 | -79 |

| Belgium | -117 | -84 | -102 | -81 |

| Canada | -19 | 10 | -19 | 0 |

| Germany | -86 | -96 | -70 | -83 |

| Netherlands | -61 | -50 | -65 | -61 |

Table 1. PISA Reading Scores 2003 and 2006 (based on data presented in Christensen and Steglitz, 2008; Gen 1 = first generation students born outside the host country, Gen 2 = second generation students born in the host country; negative scores indicate performance below country mean, positive scores indicate performance above country mean; overall mean is 500).

By contrast, second generation students tend to perform very poorly in countries that have been characterized by highly negative attitudes towards immigrants (e.g., Austria, Belgium, Germany). In some cases (Denmark and Germany in 2003; Austria and Germany in 2006) second generation students who received all their schooling in the host country performed more poorly than first generation students who arrived as newcomers and would likely have had less time and opportunity to learn the host country language. These data clearly suggest that factors other than simply opportunity to learn the host country language are operating to limit achievement among second-generation students in these countries.

Effective Instruction that Responds to Causes of Underachievement

Table 2 elaborates on the three sources of potential educational disadvantage outlined above and also specifies the evidence-based educational responses that are likely to have the highest impact in addressing these sources of potential disadvantage.

Table 2. Ways in which Schools Can Reduce the Impact of Potential Educational Disadvantage

Home-School Linguistic Differences. Two issues are relevant here: (a) To what extent does the simple fact of speaking a language other than the school language at home constitute a cause of underachievement? (b) What instructional programs or initiatives are most effective in helping students learn the school language (L2)?

Home language use and achievement. The PISA data, at first sight, appear to show a negative relationship between language spoken at home and academic achievement. In both mathematics and reading, first and second generation immigrant-background students who spoke their L1 at home were significantly behind their peers who spoke the school language at home. Christensen and Stanat (2007) conclude: “These large differences in performance suggest that students have insufficient opportunities to learn the language of instruction” (p. 3). German sociologist Hartmut Esser (2006) similarly argues on the basis of PISA data that “the use of the native language in the family context has a (clearly) negative effect” (p. 64). He further argues that retention of the home language by immigrant children will reduce both motivation and success in learning the host country language (2006, p. 34).

These interpretations of the data do not stand up to critical scrutiny. Specifically, no relationship was found between home language use and achievement in the two countries where immigrant students were most successful (Australia and Canada) and the relationship disappeared for a large majority (10 out of 14) of OECD-member countries when SES and other background variables were controlled (Stanat & Christensen, 2006, Table 3.5, pp. 200-202). The disappearance of the relationship in a large majority of countries suggests that language spoken at home does not exert any independent effect on achievement but is rather a proxy for variables such as socioeconomic status and length of residence in the host country. Beyond the PISA data, the argument that L1 use at home will exert a negative effect on achievement in L2 is refuted by the academic success of vast numbers of bilingual and multilingual students in countries around the world. Thus, parents who interact consistently with their children in L1 as a means of promoting bilingualism and biliteracy can do so with no concern that this will impede their children’s acquisition of the school language.

Effective instructional responses. The international research data strongly supports the effectiveness of bilingual education for minority group students (e.g., Gögolin, 2005). Several recent comprehensive research reviews on bilingual education for underachieving minority language students suggest that in contexts where bilingual education is feasible (e.g., high concentration of particular groups), it represents a superior option to immersion in the language of the host country. In the North American context, for example, Francis, Lesaux and August (2006) report: “The meta-analytic results clearly suggest a positive effect for bilingual instruction that is moderate in size” (p. 397). Similarly, Lindholm-Leary and Borsato (2006) conclude that minority student achievement “is positively related to sustained instruction through the student’s first language” (p. 201). Thus, bilingual education represents a legitimate and, in many cases, feasible option for educating immigrant and minority language students.

In cases where bilingual education cannot be implemented either for reasons of feasibility or ideology, then it is crucial that all teachers (not just language specialists) know how to support students in acquiring academic skills in the school language. The term scaffolding is commonly used to describe the temporary supports that teachers provide to enable learners to carry out academic tasks. These supports can be reduced gradually as the learner gains more expertise. They include strategies such as use of visuals and concrete experiences and demonstrations to increase comprehension.

Low SES. In general, the SES of individual students exerted a highly significant effect on achievement in the PISA studies: “On average across OECD countries, 14% of the differences in student reading performance within each country is associated with differences in students’ socio-economic background” (OECD, 2010a, p. 14). However, this report noted that the effect of the school’s economic, social and cultural status on students’ performance is much stronger than the effects of the individual student’s socio-economic background. In other words, when students from low-SES backgrounds attend schools with a socio-economically advantaged intake, they tend to perform significantly better than when they attend schools with a socio-economically disadvantaged intake. The different performance of schools in advantaged versus disadvantaged areas that goes beyond the SES backgrounds of students in these schools likely reflects a variety of factors including differences in teacher experience and quality.

Some of the sources of potential educational disadvantage associated with SES are beyond the capacity of individual schools to address (e.g., housing segregation) but the potential negative effects of other factors can be ameliorated by school policies and instructional practices. In this regard, the two sources of potential disadvantage that are most significant are the limited access to print that many low-SES students experience in their homes, neighborhoods and schools (Duke, 2000; Neuman & Celano, 2001) and the more limited range of language interaction that has been documented in the United States in many low-SES families as compared to more affluent families (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1995). The logical inference that derives from these differences is that schools serving low-SES students should (a) immerse them in a print-rich environment in order to promote literacy engagement across the curriculum and (b) focus in a sustained way on how academic language works and enable students to take ownership of academic language by using it for powerful (i.e., identity-affirming) purposes.

The relevance of literacy engagement is demonstrated in successive PISA studies that have reported a strong relationship between reading engagement and reading achievement. The 2000 PISA study (OECD, 2004) reported that the level of a student’s reading engagement was a better predictor of literacy performance than his or her SES. In more recent PISA studies, the OECD (2010a) reported that approximately one-third of the association between reading performance and students’ SES was mediated by reading engagement. The implication is that schools can potentially ‘push back’ about one-third of the negative effects of socioeconomic disadvantage by ensuring that students have access to a rich print environment and become actively engaged with literacy.

Marginalized Status. There is extensive research documenting the chronic underachievement of groups that have experienced systematic long-term discrimination in the wider society. The link between societal power relations and school experiences of some minority group students has been succinctly expressed by Ladson-Billings (1995, p. 485)with respect to African-American students: “The problem that African-American students face is the constant devaluation of their culture both in school and in the larger society.” This constant devaluation of culture is illustrated in the well-documented phenomenon of stereotype threat (Steele, 1997). Stereotype threat refers to the deterioration of individuals’ task performance in contexts where negative stereotypes about their social group are communicated to them. Thus, there is a clear link between societal power relations, identity negotiation, and task performance.

Among linguistically diverse students, the home language represents a very obvious marker of difference from dominant groups. Despite increasing evidence of the benefits of bilingualism for students’ cognitive and academic growth, schools in many contexts continue to prohibit students from using their L1 within the school, thereby communicating to students the inferior status of their home languages and devaluing the identities of speakers of these languages. This pattern is illustrated in a study of Turkish-background students in Flemish secondary schools carried out by Agirdag (2010). He concludes:

[O]ur data show that Dutch monolingualism is strongly imposed in three different ways: teachers and school staff strongly encourage the exclusive use of Dutch, bilingual students are formally punished for speaking their mother tongue, and their home languages are excluded from the cultural repertoire of the school. At the same time, prestigious languages such as English and French are highly valued. (p. 317)

How can schools counteract the negative effects of societal power relations that devalue minority group identities? Ladson-Billings (1994), once again, has expressed the essence of an effective instructional response: “When students are treated as competent they are likely to demonstrate competence” (1994, p. 123). In other words, educators, both individually and collectively, must challenge the devaluation of students’ language, culture, and identity in the wider society by implementing instructional strategies that enable students to develop “identities of competence” (Manyak, 2004) in the school context. These instructional strategies will communicate high expectations to students regarding their ability to succeed academically and support them in meeting these academic demands by affirming their identities and connecting curriculum to their lives.

Conclusion

Underachievement among immigrant-background students is not caused by home use of a language other than the school language. L1 use at home represents a potential source of educational disadvantage only when the school fails to provide appropriate support to enable students to develop academic skills in the school language. Underachievement is observed predominantly among linguistically diverse students who are also experiencing the effects of low-SES and/or marginalized group status in the host country. Thus, instruction must also address the sources of potential disadvantage that characterize low-SES and marginalized group students. This will include maximizing students’ engagement with literacy (ideally in both L1 and L2) and enabling them to use language powerfully in ways that enhance their academic and personal self-concept. In a social context where the identities of marginalized group communities have been devalued, effective identity-affirming instruction requires that schools challenge the societal power structures that position students as socially inferior and less capable academically. A first step in this process is for schools to acknowledge the academic, cognitive, and social value of students’ home languages and encourage them to develop literacy in these languages.

References

Agirdag, O. (2010). Exploring bilingualism in a monolingual school system: Insights from Turkish and native students from Belgian schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 31(3), 307-321. DOI: 10.1080/01425691003700540

Christensen, G. & Segeritz, M. (2008). An international perspective on student achievement. In Bertelsmann Stiftung (Ed.), Immigrant students can succeed: Lessons from around the globe (pp. 11-33). Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Christensen, G., & Stanat, P. (2007, September). Language policies and practices for helping immigrant second-generation students succeed. The Transatlantic Task Force on Immigration and Integration convened by the Migration Policy Institute and Bertlesmann Stiftung. Retrieved 15 October 2007 from http://www.migrationinformation.org/transatlantic/

Duke, N. (2000). For the rich it’s richer: Print experiences and environments offered to children in very low and very high-socioeconomic status first-grade classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 441–478.

Esser, H. (2006). Migration, language, and integration. AKI Research Review 4. Berlin: Programme on Intercultural Conflicts and Societal Integration (AKI), Social Science Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.wzb.eu/zkd/aki/files/aki_research_review_4.

Francis, D., Lesaux, N., & August, D. (2006), Language of instruction. In D. August & T. Shanahan (Eds.), Developing literacy in second-language learners. Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth (pp. 365–413). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ.

Gögolin, I. (2005). Bilingual education: The German experience and debate. In J. Söhn (Ed.), The effectiveness of bilingual school programs for immigrant children. AKI Research Review 2 (pp. 133-145). Berlin: Programme on Intercultural Conflicts and Societal Integration (AKI), Social Science Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.wzb.eu/zkd/aki/files/aki_bilingual_school_programs.pdf.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995) Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Lindholm-Leary, K. J., & Borsato, G. (2006). Academic achievement. In F. Genesee, K. Lindholm-Leary, W. Saunders, & D. Christian (Eds), Educating English language learners (pp. 176-222). New York:Cambridge University Press.

Manyak, P. C. (2004). “What did she say?” Translation in a primary-grade English immersion class. Multicultural Perspectives, 6, 12–18.

Neuman, S. B., & Celano, D. (2001). Access to print in low-income and middle-income communities: An ecological study of four neighbourhoods. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 8-26.

OECD (2004). Messages from PISA 2000. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD (2010). PISA 2009 results: Learning to learn – Student engagement, strategies and practices (Volume III). Paris: OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/11/17/48852630.pdf

Stanat, P., & Christensen, G. (2006). Where immigrant students succeed: A comparative review of performance and engagement in PISA 2003. Paris: OECD.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613-629.