Alison Smale

Veteran journalist and former UN Undersecretary General for global communications

The very selection of themes for this edition of Politeknik illustrates perhaps better than anything else could the point we have reached in our political discussions, and what we expect of our leaders, and institutions, in terms of preserving human life itself. Turning these topics into questions seems the best way to keep our discussion fresh.

So: does everyone have a right to health care? When battling a disease that has killed or infected millions, can we preserve and support democracy? Is nationalism our most powerful

unifying force in testing times? Can we sustain the way of life we have come to expect or aspire to, or will millions even in wealthy countries depend on food banks and other charity? Will that kind of basic need diminish our force and creativity, sorely needed to solve challenges like climate change?

Each question posed above cannot be weighed in isolation. But writing as I do from New York, the self-proclaimed media capital of the world, the city that never sleeps that is right now living through a nighttime curfew, I will focus on the most fundamental: can we preserve democracy?

If the measure of freedom is one’s ability to speak truth to power without getting locked up, then the United States and its 300 million people are still well off. I am writing days after

President Donald Trump called on America’s governors not to be “weak,” but to “dominate” following protests and violence in scores of communities, triggered by the unspeakable end of George Floyd, an unarmed black man killed by four police offi cers in Minneapolis.

The president himself led a handful of his top advisers to a church near the White House, apparently for a photo op with a Bible – with his path cleared by police acting on the Administration’s orders. The reaction was swift; current and former military commanders and civilians at the Pentagon closed ranks and vowed to defend their institution – America’s most respected, according to opinion polls – against what The New York Times columnist Paul Krugman suggested was the “weaponization” of racism. Jim Mattis, Mr. Trump’s fi rst secretary of defense, issued a withering attack on the president, saying that “Donald Trump is the fi rst president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people – does not even pretend to try.” Instead, “he tries to divide us. We are witnessing the consequences of three years of this deliberate effort. We are witnessing the consequences of three years without mature leadership.”

Around the world, there are many countries where such criticism of the powers-that-be would lead to instant incarceration, or worse. But Americans measure their freedom by their own standards, the fruit of almost 250 years of rule by law, and not by use of the military to uphold law and order. Indeed, there were also hopeful signs emerging from the tumult that convulsed many US communities after the killing of Mr. Floyd. In New York, for instance, the most senior uniformed police offi cer, Terence Monahan, knelt with leaders of the protest against Mr. Floyd’s killing –a genufl ection that mayor Bill de Blasio labeled a “signifi cant moment of change” in relations between the cops and the communities they patrol and work with.

It will take many more such efforts to heal the deep wounds left by 400 years of racism. But New York had already shown its ability to prevail over adversity by its response to the colossal challenge of the pandemic. Covid-19 is a worldwide scourge, against which scientists, politicians, business people and billions of others must unite if they are to devise a treatment, a vaccine, a cure. The disease arrived in the United States rather quietly. Perhaps because the fi rst reports from China of a new, unidentifi ed lurgy came as much of the world was celebrating Christmas and then New Year, there was little fanfare, or sense of shock and peril, at first.

The now familiar timeline of the disease spreading to Europe and the western United States and then to the East Coast meant that even as late as the end of February, alarm was still somewhat muted. But then the full force of what was needed to battle this diffi cult new enemy became clear. It involved basically shutting down life as routinely lived in much of the world. Systems we imagined were built for the ages turned out to be fragile in the face of disease. Human beings were resourceful and resilient – how else would the heroic health workers of hospitals worldwide have succeeded in fl attening the curve? – but rearranging life to make it truly sustainable will require many more efforts than those we have seen to date.

Where do we go from here, in fact? It has been instructive to watch the response of communities large and small. Even within medium-sized towns, they often differ. One big test

for democracy in this age of Covid-19 will be the ability to unite in a sustained fashion. It will involve also adjusting to the warp speed of technology vs. the much slower pace at which human beings absorb and act on new information.

The big debate over the future of tech is only now unfurling in its true, enormous, dimensions. While the Mark Zuckerbergs and Jack Dorseys of this world wrangle with governments and the ordinary people who control and consume tech, social media will be already deployed to create the next protest, or political demand, in ways that lie outside the framework we have built to manage our affairs to date. Who will judge, or verify, which of these structures is suitable for the challenges ahead? How will we determine that any new political frameworks are workable, or fair?

All these questions form the legacy today’s young people – the most numerous ever – are inheriting. How will we frame the communication between this new generation and the older grayhairs scorned by the likes of teenage activist Greta Thunberg? Aside from the question of age, what are the measuring sticks of a successful discussion and development of absolutely new ways of working and organizing? How much importance should we continue to attach, for instance, to the nation state as a sensible form of human activity?

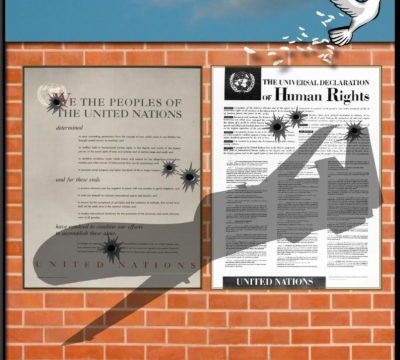

Almost every analyst of the current situation mentions the need for international cooperation if we are to extricate ourselves from our current plight. Yet the record of such cooperative efforts falls far short of the lofty aims articulated by their founders. The United Nations is much maligned, indeed neglected, by its founding members if they perceive no collaborative success or individual advantage in using the organization for the purposes for which it was established. Which leaves the UN looking often slightly quaint, a kindly aunt offering wise but outdated counsel as the new Masters of the Universe proceed to invent new tasks in a virtual world that poses questions you never knew existed, let alone needed to be solved.

Which returns us to our original question: can we preserve democracy and at the same time advance? The United States has always answered in the affi rmative. But the United States has also come up short in recent years, and is now arguably broken. As the eruption over George Floyd’s murder showed, American racism bears many distinctive characteristics, but there is an even broader anger at work. In threatening the wealth and well being of Americans, it could paralyze America at a time when its vitality is a prerequisite for pulling together. If America is no longer available to lead the world, we must all keep watch on who enters the void that remains. China, as the #2 world economy, is usually identified at this stage as the likely candidate for domination. Yet while determined and rapid, China’s rise

is still far from matching America’s strength. The United States is powerful yet. Its friends (and even its foes) can only hope that it decides to rekindle alliances and associations in time to fight what James Baldwin so eloquently called “The Fire Next Time.”